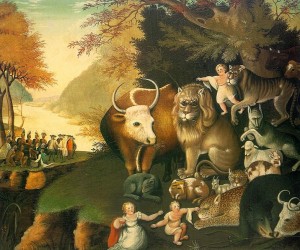

From 1820 until his death in 1849, the Quaker preacher and artist Edward Hicks painted about a hundred different depictions of this same scene—likely you have seen one or more of them. In each painting, children stand unafraid among lions, wolves, and bears, accompanied by sheep and cattle. Every face, human and animal, gazes calmly out of the canvas, meeting our eyes in serene invitation. To each painting, Hicks gave the same title: “The Peaceable Kingdom.”

Hicks’ imagery is drawn directly from the prophet Isaiah:

The wolf will live with the lamb,

and the leopard will lie down with the young goat;

the calf and the young lion will feed together,

and a little child will lead them (Isa 11:6).

But Isaiah’s vision of the peaceable kingdom, charmingly reflected in Hicks’ paintings, is itself drawn from Genesis 1:29-30 (CEB):

Then God said, “I now give to you all the plants on the earth that yield seeds and all the trees whose fruit produces its seeds within it. These will be your food. To all wildlife, to all the birds in the sky, and to everything crawling on the ground—to everything that breathes—I give all the green grasses for food.” And that’s what happened.

Genesis 1:1—2:4a depicts a peaceful, ordered world, in which conflict has no place. But as we have seen, that ordered world emerges out of disorder: “When God began to create the heavens and the earth— the earth was without shape or form, it was dark over the deep sea, and God’s wind swept over the waters” (Gen 1:1-2).

Before creation, there was chaos: imagined here as formless, shapeless water. Israel shared this notion of the world emerging out of watery chaos with its ancient neighbors.

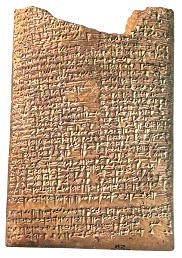

The Babylonian creation epic Enuma elish opens with these words:

When on high the heaven had not been named,

Firm ground below had not been called by name,

Naught by primordial Apsu, their begetter

(And) Mummu-Tiamat, who bore them all.

In Akkadian, the language of the Babylonians, apsu refers to the waters under the earth, the fresh water reservoir out of which all streams and springs emerge. Our word “abyss” comes (by way of the Greek abyssos) from this Akkadian root: apsu is the deep, the fresh-water abyss. The counterpart to the male Apsu is the female Tiamat, which in Akkadian means “salt water.” Tiamat is, quite literally, the sea monster.

According to the Enuma Elish, out of this merging of fresh water and salt water, the union of Apsu and Tiamat, the gods were born. Soon thereafter, their father Apsu tired of the gods and decided to destroy them. But the gods found out about Apsu’s plan, and advised by Ea, the god of wisdom, they killed their father. In wrath their mother, Tiamat, swore to destroy her children. Tiamat is imagined as a dragon: an invulnerable serpent thing armored with scales. The gods realize that they cannot prevail against her separately, and so they elect one of their number as king over the gods, and pour all of their power into that one chosen champion. Marduk, patron god of Babylon, was elected king and, suffused with the power of the other gods, succeeded in confronting and defeating the monster of chaos.

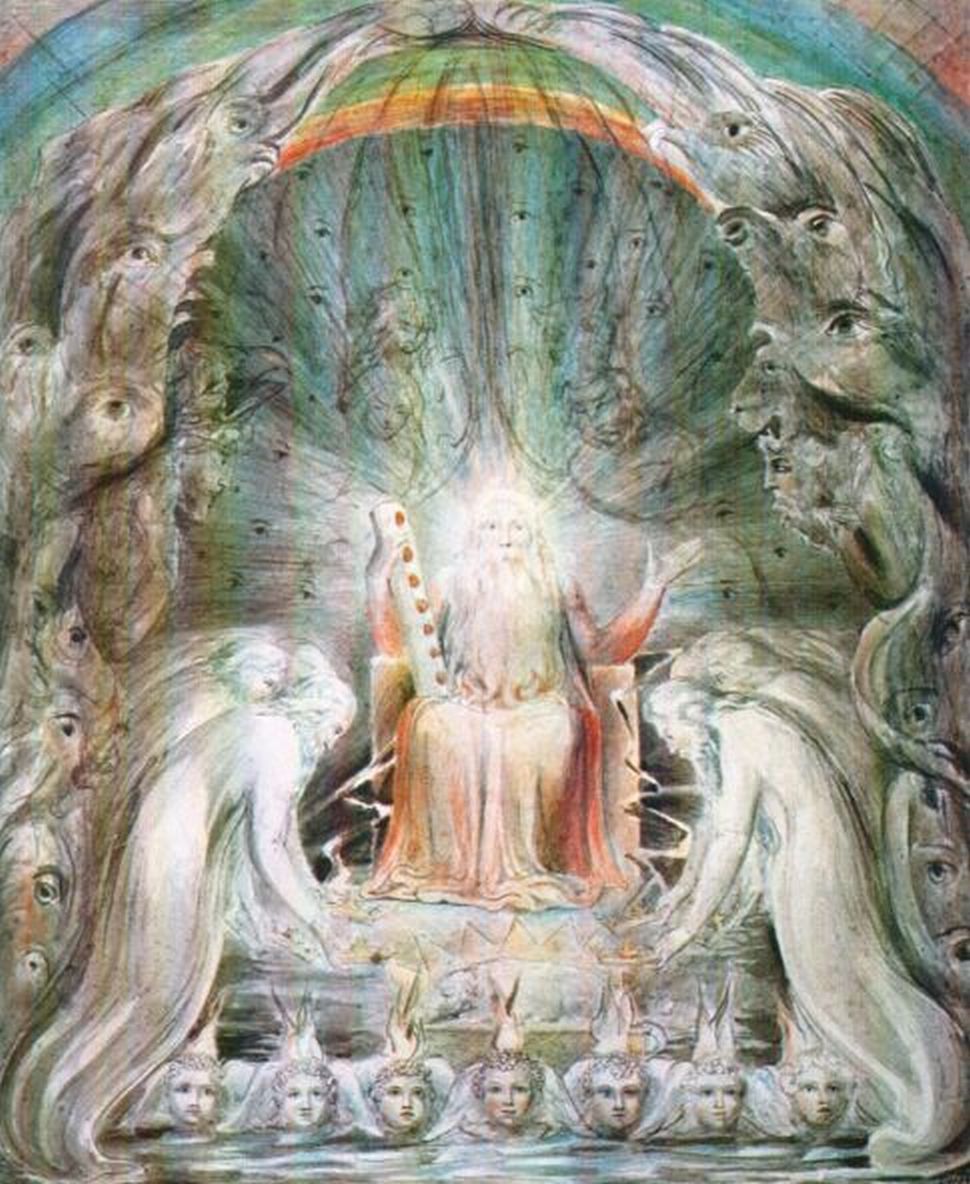

But Genesis 1 imagines the beginning in a very different way. Here, there is no combat. Chaos has no will to oppose to God’s.

In serene, sovereign majesty God speaks the universe into existence: “God said, “Let there be light.” And so light appeared.” (Gen 1:3).

The creation of light is described as an act of separation: “God separated the light from the darkness” (Gen 1:4). As Claus Westermann (Genesis: A Practical Commentary, trans. David Green [Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 1987], pp. 8-9) observed, the first three days of creation all involve acts of separation: light from darkness; waters above from waters below; dry land from water. The Hebrew word used here, hibdil, is important in priestly vocabulary. One of the primary tasks of priests in ancient Israel was to teach their people to keep the holy separate from the common, the clean from the unclean (Lev 10:10). As separation (hibdil) was a priestly concept in ancient Israel, it seems likely that we are dealing in Genesis 1:1—2:4a with a priestly worldview.

God not only separates the light from the darkness, but also gives them both familiar, and significant, names:

God named the light Day and the darkness Night. There was evening and there was morning: the first day (Gen 1:5).

It is not that God created light on the first day, then, but rather that by creating light and separating it from the darkness, God created the first day. To put this another way, God brings time into being.

Now that there has been a first day, there can be a second, and a third, and a fourth, and so on, through all the days that will follow. With the creation of light, the cosmic clock begins ticking. In this priestly composition, God stands outside of time itself, and calls it into being.

Day two is also an act of separation:

God said, “Let there be a dome in the middle of the waters to separate the waters from each other.” God made the dome and separated the waters under the dome from the waters above the dome. And it happened in that way. God named the dome Sky. There was evening and there was morning: the second day (Gen 1:6-8).

The Hebrew word for the sky dome is raqiya’, which means literally “something beaten out:” much as, in the ancient world, a bronze bowl was beaten out of a sheet of bronze.

The King James translation “firmament” captures this notion very well. The sky is a solid object! God takes this dome and inserts it into the waters of chaos, much as we might plop a bowl upside-down into the sink while washing the dishes. Of course, when you take a bowl and stick it in the water, a bubble of air can be trapped inside. Just so, when God inserts the sky dome into the waters of chaos, there is water is above the dome and water below, but inside the dome there is an open space where creation can take place.

In the Enuma Elish, after Marduk defeated Tiamat,

Then the lord paused to view her dead body,

That he might divide the form and do artful works.

He split her like a shellfish into two parts:

Half of her he set up as a covering for heaven,

Pulled down the bar and posted guards.

He bade them to allow not her waters to escape.

While the connection between Genesis 1:6-8 and the Enuma elish is apparent, there is also a clear distinction between the worldview of Israel’s priests and that of ancient Babylon. The violence in the account of creation through primordial combat is entirely absent from Genesis 1. God simply speaks an ordered world into being!

If day one, with the creation of light and the separation of light from darkness, marked the creation of time, day two marks the creation of space. Now there is up and down, right and left, back and forth. Order is beginning to emerge out of the chaos.

The notion that time and space have a beginning is certainly not obvious. Many world religions and philosophies assert that the universe has always existed, and indeed until the mid-twentieth century, this was the common assumption of science as well. But Genesis 1 asserts that God stands outside of both time and space, and calls them into being.

The priestly assertion that space and time have a beginning is consonant with the insights of contemporary physics. Based on observations of the expansion of the universe, astrophysicists extrapolate backwards to a moment when our universe was compacted into a point, called a singularity. Observation and measurement of a residual background radiation, detectable in every direction, suggests that our universe exploded out of that singularity in what is prosaically referred to as the “Big Bang.”

With that cataclysmic explosion, space came into being. Our universe is not expanding into something; rather, space comes into being as the universe expands. This concept is difficult enough to grasp.

However, Einstein demonstrated that time is not an absolute quantity apart from space, but is itself a “direction” or dimension, related to movement through space: the faster we go, the slower time passes. This is why contemporary physics refers not to space and time, but to space-time. The Big Bang marks, then, not only the beginning of space, but the beginning of time as well. As Israel’s ancient priests affirmed, there was indeed a first day.

This does not mean that the priests were doing science. After all, we know that the sky is not, and has never been, a solid bowl! Still, the consonance between contemporary cosmology’s discovery of a beginning to space-time and the theological assertion in Genesis 1 that God created time and space shows that these two ways of understanding our world are not at odds with one another. Christians need not choose between science and faith; nor do we need to invent our own uniquely Christian ways of doing science, in competition with “secular” science. Points of consonance such as the Big Bang remind us that there is after all one world, described by science and faith alike, which we all inhabit and attempt to understand.

Next week we will continue to consider the beauty of creation as presented in the first chapters of Genesis, beginning with the third day.