Sunday is Pentecost, which means that bewildered lay readers (and more than a few preachers!) across the church will once again be wrestling with the jawbreaking, tongue-tangling list of place names (go here for pronunciation help) in Acts 2:7-11.

Sunday is Pentecost, which means that bewildered lay readers (and more than a few preachers!) across the church will once again be wrestling with the jawbreaking, tongue-tangling list of place names (go here for pronunciation help) in Acts 2:7-11.

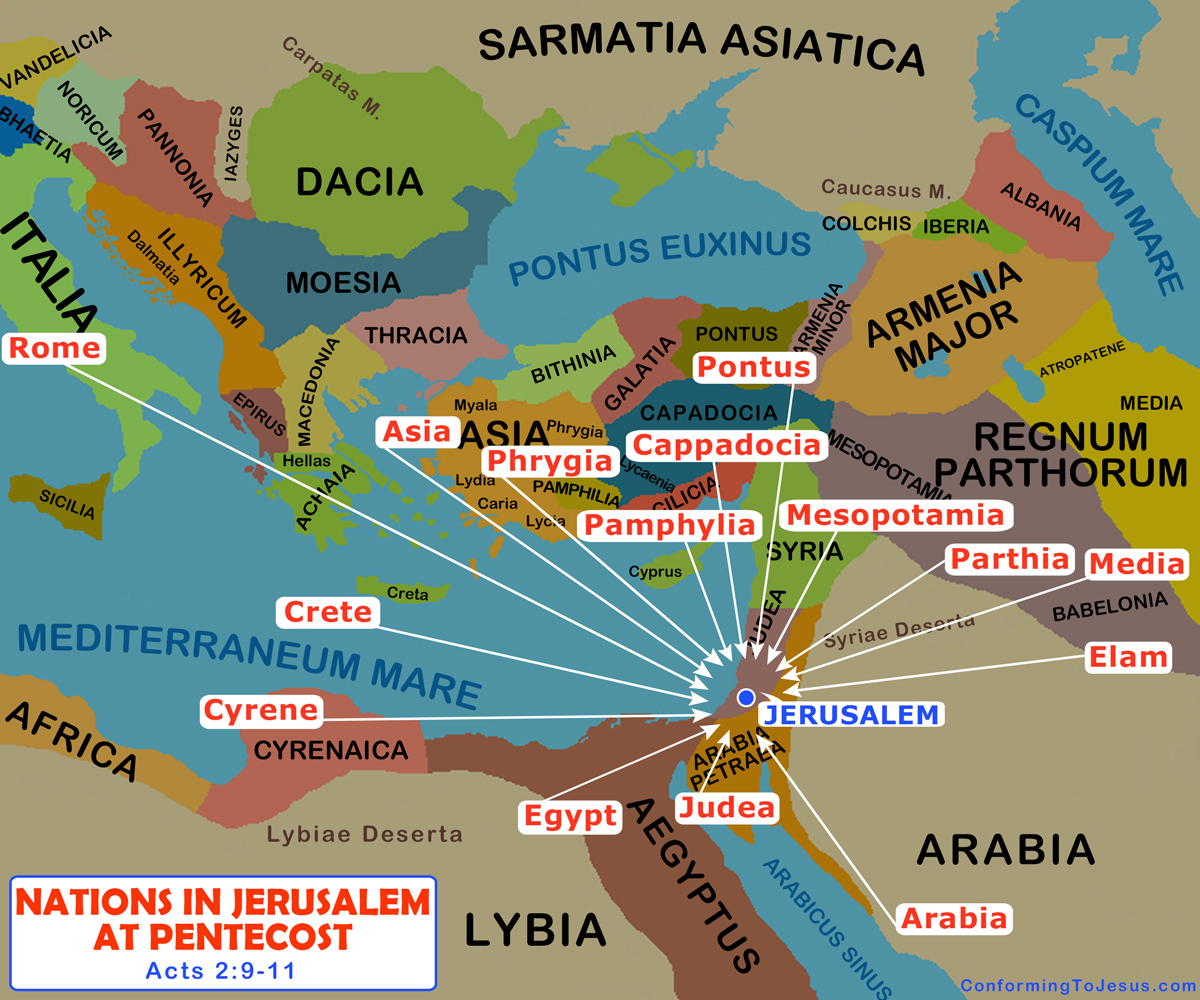

They were surprised and amazed, saying, “Look, aren’t all the people who are speaking Galileans, every one of them? How then can each of us hear them speaking in our native language? Parthians, Medes, and Elamites; as well as residents of Mesopotamia, Judea, and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the regions of Libya bordering Cyrene; and visitors from Rome (both Jews and converts to Judaism), Cretans and Arabs—we hear them declaring the mighty works of God in our own languages!”

This concatenation of unfamiliar (to us, at least) places makes an important point. Pentecost (called Shavuot, or the Feast of Weeks, in Judaism) was one of the pilgrim feasts, when Jews able to make the journey were to come to Jerusalem for the celebration (Deuteronomy 16:16; Exodus 23:14-17; 34:18-23). So Jewish pilgrims from all over the Roman world (and, in the case of the Parthians at least, even from beyond the empire) were gathered for Pentecost in Jerusalem’s streets.

Meanwhile, Jesus’ followers were waiting in Jerusalem as he had commanded them (Luke 24:49), praying in an upper room.

Meanwhile, Jesus’ followers were waiting in Jerusalem as he had commanded them (Luke 24:49), praying in an upper room.

Suddenly a sound from heaven like the howling of a fierce wind filled the entire house where they were sitting. They saw what seemed to be individual flames of fire alighting on each one of them. They were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other languages as the Spirit enabled them to speak (Acts 2:1-4).

Boiling out of the upper room and into the streets, Jesus’ followers crashed into that polyglot crowd–and those pilgrims from distant lands discovered, to their astonishment, that they could understand these Galileans perfectly: “’we hear them declaring the mighty works of God in our own languages!’” (Acts 2:11).

Luke’s account of Pentecost plainly alludes to the Babel story in Genesis 11:1-9. But too often, preachers and teachers of Scripture (including me!) have described what happened on Pentecost as undoing the curse of Babel, as though cultural, racial, and linguistic diversity were problems to overcome. But that is not at all what Luke says! This passage does not say that the people all started speaking the same language—that their cultural and ethnic distinctiveness was denied or undone. The Spirit does not return them to “one language and the same words” (Genesis 11:1). Instead, each group hears God’s praise in its own language.

We should not be surprised that the members of the Pentecost crowd all hear the Gospel in their own languages. The entire Bible models for us how to escape what Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls the danger of a single story. Scripture rarely gives us a single story about anything! At the beginning of our Bible, we find two different accounts of the creation of the world (Genesis 1:1—2:4a and Genesis 2:4b-25). Our New Testament opens with four gospels, presenting four quite different accounts of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection.

Scripture itself, by its very structure, calls for us to listen with open ears and open hearts for the truth told, not as a single story, but as a chorus of voices. Sometimes those voices are in harmony, sometimes they are in dissonance, but always they are lifted in praise to the God who remembers all our stories, the comedies and tragedies alike, and catches them up together in love, forgiveness, and grace–as Luke’s account of Pentecost goes on to show.

Peter responds to the confused crowd’s questions with a sermon (Acts 2:17-21) based on a remarkable little book of prophecy, the book of Joel:

After that I will pour out my spirit upon everyone;

your sons and your daughters will prophesy,

your old men will dream dreams,

and your young men will see visions.

In those days, I will also pour out my

spirit on the male and female slaves.

I will give signs in the heavens and on the earth—blood and fire and columns of smoke. The sun will be turned to darkness, and the moon to blood before the great and dreadful day of the Lord comes. But everyone who calls on the Lord’s name will be saved (Joel 2:28-32 [Hebrew 3:1-5]).

The setting for Joel is a locust plague, which has decimated Judah. After the swarm has passed, and the locusts all are gone, reassurance is offered to the community, the “children of Zion” (Joel 2:23), who twice are promised, “my people shall never again be put to shame” (Joel 2:26, 27).

But Joel’s audience also learns that they are part of a larger community than they had realized. The “children of Zion,” called “my people” by the Lord, turn out to include far more than the adult men of the worshipping congregation! Women, children, the aged, slaves: all are a part of God’s congregation, upon whom God will pour out God’s Spirit–and as my dear friend and former pastor Ron Hoellein often says, “All means all.” The Hebrew Bible emphasizes the importance of this affirmation by a chapter break: Joel 2:28-32 in our English Bibles (following the Latin Vulgate) is Joel 3:1-5 in Hebrew (the English Bible’s chapter 3 is Joel 4 in the Hebrew Bible).

Joel reminds us that we too belong to a larger community than we had realized. We may have forgotten that—I confess that often I have forgotten that. We succumb to the temptation to define our community too narrowly, as including only those like us, whether ethnically or ideologically or theologically.

This Pentecost weekend marks the gathering of the United Methodist annual conference in Western Pennsylvania, a meeting held in the shadow of schism, as many of our churches will likely join the newly-formed Global Methodist Church.

Also this weekend, the Pittsburgh Pride march will be held on Saturday, in support of LGBTQ+ folk: a striking juxtaposition, as the new Methodist denomination is forming in large part to escape the continuing controversy in United Methodism surrounding the full inclusion of those very persons.

There may be no stopping that schism. But in the days and weeks to come, friends, we must learn to listen to one another—not to agree, necessarily, but to listen, to learn, and to understand. Like Joel’s audience, and Peter’s centuries later, we today need to hear God’s promise of deliverance and freedom from shame. But we cannot experience those blessings separately and severally. They are not offered to us in that way. God calls us, not to homogeneity, but to unity in diversity. We must find our salvation together.