This week’s Gospel is a parable of Jesus unique to Luke, much like those perennial favorites the Good Samaritan or the Prodigal Son. But unlike those stories of Jesus, this one is unlikely to be anyone’s favorite:

Jesus also said to the disciples, “A certain rich man heard that his household manager was wasting his estate. He called the manager in and said to him, ‘What is this I hear about you? Give me a report of your administration because you can no longer serve as my manager.’ The household manager said to himself, What will I do now that my master is firing me as his manager? I’m not strong enough to dig and too proud to beg. I know what I’ll do so that, when I am removed from my management position, people will welcome me into their houses. One by one, the manager sent for each person who owed his master money. He said to the first, ‘How much do you owe my master?’ He said, ‘Nine hundred gallons of olive oil.’ The manager said to him, ‘Take your contract, sit down quickly, and write four hundred fifty gallons.’ 7 Then the manager said to another, ‘How much do you owe?’ He said, ‘One thousand bushels of wheat.’ He said, ‘Take your contract and write eight hundred.’ (Luke 16:1-7)

Why does Jesus tell this strange story? His point seems, if anything, stranger still:

And his master commended the dishonest manager because he had acted shrewdly; for the children of this age are more shrewd in dealing with their own generation than are the children of light. And I tell you, make friends for yourselves by means of dishonest wealth so that when it is gone, they may welcome you into the eternal homes (Luke 16:8-9, NRSV).

Yup. That’s what it says. Jesus said “make friends for yourselves by means of dishonest wealth so that when it is gone, they may welcome you into the eternal homes.” What are we to do with that?

When I was a brand-new pastor, fresh out of seminary, I came into a Bible study at one of my churches, looking at the parables of Jesus. Some of the folk in that study were using the Living Bible–a popular paraphrase of Scripture into everyday language that had been my own favorite Bible as a young Christian. But to my astonishment, here is what the Living Bible did with this saying of Jesus:

But shall I tell you to act that way, to buy friendship through cheating? Will this ensure your entry into an everlasting home in heaven? No! For unless you are honest in small matters, you won’t be in large ones. If you cheat even a little, you won’t be honest with greater responsibilities.

But shall I tell you to act that way, to buy friendship through cheating? Will this ensure your entry into an everlasting home in heaven? No! For unless you are honest in small matters, you won’t be in large ones. If you cheat even a little, you won’t be honest with greater responsibilities.

That “NO!” was not in my Bible–nor, I quickly discovered, was it in the Greek text of Luke. Kenneth Taylor, who authored this paraphrase, justifies this extraordinary reading in a footnote:

Luke 16:9 [reads] . . . literally, and probably ironically, “Make to yourselves friends by means of the mammon of unrighteousness; that when it shall fail you, they may receive you into the eternal tabernacles.” Some commentators would interpret this to mean: “Use your money for good, so that it will be waiting to befriend you when you get to heaven.” But this would imply the end justifies the means, an unbiblical idea.

In other words, I don’t believe that Jesus would have said this, therefore he didn’t. But surely, that is no way to read Scripture!

I found no more help in Eugene Petersen’s popular contemporary paraphrase, The Message. Petersen reframes Luke 16:8-9 as follows:

Now here’s a surprise: The master praised the crooked manager! And why? Because he knew how to look after himself. Streetwise people are smarter in this regard than law-abiding citizens. They are on constant alert, looking for angles, surviving by their wits. I want you to be smart in the same way—but for what is right—using every adversity to stimulate you to creative survival, to concentrate your attention on the bare essentials, so you’ll live, really live, and not complacently just get by on good behavior.

Now here’s a surprise: The master praised the crooked manager! And why? Because he knew how to look after himself. Streetwise people are smarter in this regard than law-abiding citizens. They are on constant alert, looking for angles, surviving by their wits. I want you to be smart in the same way—but for what is right—using every adversity to stimulate you to creative survival, to concentrate your attention on the bare essentials, so you’ll live, really live, and not complacently just get by on good behavior.

This is interesting–and certainly, less offensive! But to me it seems too clever by half–particularly since this paraphrase makes no mention at all of the “dishonest wealth” that is the most troubling part of this saying, and that seems after all to have been the point of the parable.

If like me you grew up with the King James version, you may be aware that in that Bible translation, a strange old word appears:

And the lord commended the unjust steward, because he had done wisely: for the children of this world are in their generation wiser than the children of light. And I say unto you, Make to yourselves friends of the mammon of unrighteousness; that, when ye fail, they may receive you into everlasting habitations.

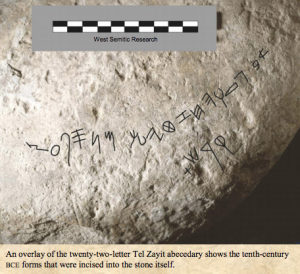

The word mammon was never an English word. Rather, it has been carried over untranslated from the Greek text, just as it was left, untranslated, in the Latin Vulgate. But mammon isn’t a Greek word, either. It comes from Aramaic, the language of first-century Palestinian Jews, and so the language that Jesus spoke. Matthew, Mark, and John preserved numerous words and phrases in Aramaic—but Luke typically did not! For example, in Luke the place Jesus is crucified is not called Golgotha (Aramaic for “skull;” see Matt 27:33; Mark 15:22; John 19:17), but Kranion (Greek for “skull;” see Lk 23:33); traditionally rendered, following the Latin Vulgate, as “Calvary” (Latin for “skull”).

The Aramaic word “mammon” means, as we can guess from its context in today’s passage, “wealth”—but generally, it was used in a negative sense. It is found only four times in the Bible: once in Matthew 6:24, and, curiously, three times in today’s reading from Luke: 16:9, 11, and 13 (//Matt 6:24). Why should Luke, who generally avoids Aramaic terms, uncharacteristically use this word, in this place? To answer that question, we need to know a bit more about Luke.

The gospel of Luke is the first volume of a two-volume work–part two is our book of Acts. Luke writes in excellent Greek, for an educated, Greek-speaking audience. Clearly, Luke was well educated, which cost money. Both Luke and Acts open with greetings to Luke’s patron, Theophilus. Evidently, Theophilus was funding Luke’s travels and research as he wrote his account of the life of Jesus and the growth of the early church. In sum: Luke comes from money; his project is funded by a patron with money, and he addresses himself primarily to an audience with money.

Yet, a major theme of Luke’s gospel is the community’s responsibility to the poor. His gospel begins with a song sung by Mary when she learns that she has been chosen to bear the Christ:

[God] has pulled the powerful down from their thrones

and lifted up the lowly.

He has filled the hungry with good things

and sent the rich away empty-handed (Lk 1:52-53).

So too, in Luke’s version of the beatitudes, we read, “Happy are you who are poor, [rather than, as in Matthew 5:3, “poor in spirit”] because God’s kingdom is yours” (Lk 6:20 ), counterbalanced by “But woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation (Lk 6:24). Indeed, next week’s gospel is another parable unique to Luke, the story of the rich man and the poor beggar Lazarus (Lk 16:19-31).

It is hard to avoid the conclusion, then, that the point of today’s parable is money, and what we are to do with it. Luke was writing to a well-off community—much like the church in the US today. To address the issue of wealth, he deliberately uses the unfamiliar Aramaic word “mammon:” a strange, but authoritative word–a Jesus word, from Jesus’ own native tongue. Luke assumes that his community is smart enough to deduce from context, as we can, that “mammon” means “wealth,” but he adds the Greek adjective adikias (rendered “dishonest” in the NRSV; “unrighteous” in the KJV) to let his community know that wealth is used here in a negative way: both the CEB and NIV have “worldly wealth,” which I think captures Luke’s point quite nicely.

By telling this parable, Jesus certainly isn’t commending the manager’s dishonesty—he doesn’t say that we should get worldly wealth that way that this man does. Rather, Jesus says, here is what we are to do with our wealth!

Whoever is faithful with little is also faithful with much, and the one who is dishonest with little is also dishonest with much. If you haven’t been faithful with worldly wealth, who will trust you with true riches? If you haven’t been faithful with someone else’s property, who will give you your own? (Lk 16:10-12).

If we are not faithful with worldly wealth, how can we expect to be trusted with heavenly?

Jesus stands here in the prophetic tradition of Amos:

Hear this, you who trample on the needy and destroy

the poor of the land, saying,

“When will the new moon

be over so that we may sell grain,

and the Sabbath

so that we may offer wheat for sale,

make the ephah smaller, enlarge the shekel,

and deceive with false balances,

in order to buy the needy for silver

and the helpless for sandals,

and sell garbage as grain?”

The LORD has sworn by the pride of Jacob:

Surely I will never forget what they have done (Amos 8:4-7).

Those Amos condemns cheat the poor so as to multiply their own riches, as though wealth were an end in itself. For them, the purpose of money is to make more money, by any and every means possible. With Amos, Jesus condemns this attitude: “No slave can serve two masters; for a slave will either hate the one and love the other, or be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and wealth” (Matt 6:24//Lk 16:13).

The dishonest manager in Jesus’ story may be a scoundrel, but at least he knows what money is for! In Jesus’ parable, the manager spends his wealth (well, actually, his master’s [!]) to reduce others’ debts, to ease their burdens–to “make friends.” Only if we spend our money in that way, Jesus affirms, will our wealth make any difference in this world–and certainly, only in that way will our wealth make any difference to us in the world to come, as we cannot take it with us!

John Wesley preached his famous sermon, “On the Use of Money,” based on this very difficult text. His conclusion was very simple: first, “Christian prudence” means to “Gain all you can” and “Save all you can.” However, this is scarcely the beginning:

But let not any man imagine that he has done anything, barely by going thus far, by “gaining and saving all he can,” if he were to stop here. All this is nothing, if a man go not forward, if he does not point all this at a farther end. Nor, indeed, can a man properly be said to save anything, if he only lays it up. You may as well throw your money into the sea, as bury it in the earth. And you may as well bury it in the earth, as in your chest, or in the Bank of England. Not to use, is effectually to throw it away. If, therefore, you would indeed “make yourselves friends of the mammon of unrighteousness,” add the Third rule to the two preceding. Having, First, gained all you can, and, Secondly saved all you can, Then “give all you can.”

Here, I think, Wesley has grasped very neatly the point of this difficult parable. Wealth is not an end to itself. Mammon is not to be our master, but our servant: it is meant to be used, to ease another’s burden, to heal another’s pain. We get it so that we can give it away. That’s what it’s for.

FOREWORD: I am reposting this from 2018. Happy Epiphany, friends!

FOREWORD: I am reposting this from 2018. Happy Epiphany, friends!

Can we be certain that the wheel will turn and that the cycle will continue? In short: does the world make sense?

Can we be certain that the wheel will turn and that the cycle will continue? In short: does the world make sense?

/salisbury-cathedral-choristers-prepare-for-christmas-502171608-57def2aa5f9b5865165118c9.jpg)

Come join us at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary as we host a community Fall Festival and Trunk-r-Treat, Saturday October 26, 5:00-8:00 pm! The event is free and open to the public. All are welcome! There will be trunk-r-treating, food, carnival activities, pumpkin painting, fall games, smores, 50/50 raffle, and so much more! My only beef is that they called it a Fall Festival, rather than rejoicing in the ancient Christian connections of All-Hallows Eve!

Come join us at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary as we host a community Fall Festival and Trunk-r-Treat, Saturday October 26, 5:00-8:00 pm! The event is free and open to the public. All are welcome! There will be trunk-r-treating, food, carnival activities, pumpkin painting, fall games, smores, 50/50 raffle, and so much more! My only beef is that they called it a Fall Festival, rather than rejoicing in the ancient Christian connections of All-Hallows Eve!

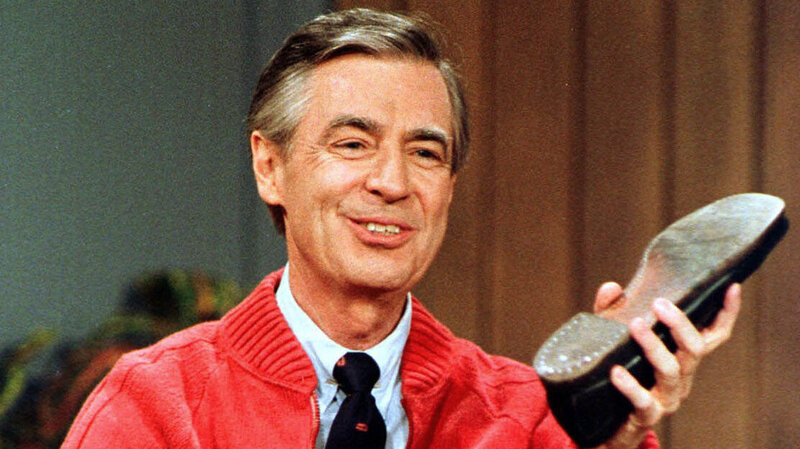

Certainly, Mr. Rogers took some flack for his message of self-affirmation. One television panel claimed that this message was “

Certainly, Mr. Rogers took some flack for his message of self-affirmation. One television panel claimed that this message was “