![Title: Lift Every Voice and Sing, or, The Harp

[Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/lift-every-voice8927xc.jpg)

FOREWORD: I am re-sharing this post (slightly edited) from last year, regarding what Juneteenth is, and why it matters to us all. Pray, friends, for peace with justice, and for the willingness to let God send us forth, giving those prayers hands and feet and a public voice.

June 19th has long been a famous day in the African-American community, where it is remembered and celebrated as “Juneteenth.” In recent days, more and more white Americans have been brought to realize the significance of this day, as tragic events have brought forcefully and painfully to our national attention America’s original sin of racism and injustice. Juneteenth recalls June 19, 1865, when Union soldiers, led by Major General Gordon Granger, landed at Galveston, Texas with news that the war was over, and that the enslaved were now free. This was over two months after the surrender of General Robert E. Lee on April 9, 1865, and two and a half years after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, delivered on January 1, 1863. Yet Black Americans in Galveston remained enslaved until the arrival of General Granger’s regiment overcame local resistance to the idea of liberation.

General Granger issued General Order Number 3, which began:

The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and free laborer.

Perhaps we should not be surprised that freedom came so late to Galveston. After all, while the decades following the Civil War saw the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, promising freedom and equality, they also saw the betrayal of that promise, as with at best the indifference, and at worst the connivance of the federal government, the rights that the Constitution conveyed to all Americans were denied.

Whatever the Constitution said, the social norms of white supremacy were codified in Jim Crow laws, and enforced by horrific violence. The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama honors the memory of more than 4,400 black people lynched in the United States–hanged, burned, murdered, tortured to death– between 1877 and 1950.

That legacy of violence is not past. In this past year alone, the lynching of Ahmaud Arbery, the police killings of Breonna Taylor and Rayshard Brooks, and most of all, the horrific videos of George Floyd‘s public murder by a Minneapolis police officer, prompted not only a national, but a world-wide outcry against racial injustice and police brutality. Yet sadly, even as justice has prevailed in some of these cases, it remains deferred in others–while new acts of racist violence continue to arise.

Some readers of this blog may be wondering what any of this has to do with the Bible, which is after all the subject of this blog. That, as it happens, is a very good question. It is no accident that nineteenth-century abolitionists did not base their arguments on Scripture. The bulk of the biblical witness seemed to be on the opposite side of the issue–indeed, African slavery was justified then on biblical grounds. After all, both testaments assume the existence of slavery, and the New Testament repeatedly urges slaves to be obedient to their masters (Eph 6:5; Col 3:22; 1 Peter 2:18).

While I was studying for my doctorate at Union Theological Seminary in Virginia, my library carrel was for a time near a tall shelf of books written by Bible scholars teaching and writing at that distinguished Southern school in the years prior to the Civil War. Their books noted, rightly, that the Bible never challenges the institution of slavery. Indeed, some argued that slavery had been a boon for the African people, civilizing these savages and introducing them to the Christian gospel.

What those white antebellum Bible scholars could not see, but new African American Christians could, were texts such as Paul’s statement, “There is neither Jew nor Greek; there is neither slave nor free; nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3:28). Somehow those distinguished Bible scholars could not see that the heart of the Hebrew Bible–called by philosopher Emil Fackenheim the “root experience” of the Jewish people–was the exodus out of Egypt: God’s action to set slaves free. Sadly, it still remains possible for us to read the Bible from cover to cover and somehow miss the passion for justice that runs like a river from Genesis to Revelation. Similarly, in white America, racism remains invisible to those who, thanks to white privilege, do not–or cannot–see it, over 150 years after that first Juneteenth.

Community and equality, cooperation and justice, mutual respect and mutual regard are biblical principles. Far from being unreachable ideals, they are the only way that the world truly works, reflecting the identity of the Creator, who is in Godself a community of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. When any culture elevates one person, class, or race over another, and exalts taking and having over giving and sharing, life itself breaks down. No wonder our economy, our world, and our church are in trouble!

AFTERWORD:

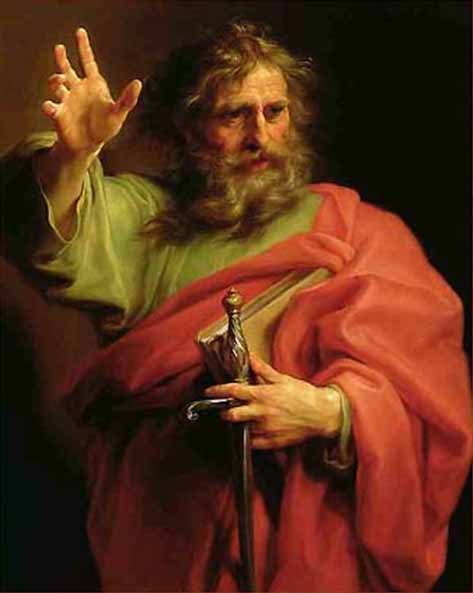

The photograph at the head of this blog is from “Art in the Christian Tradition,” an on-line gallery linked to the lectionary, managed by The Vanderbilt Divinity School Library. The image comes from The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP, April 1939. The sculpture by Augusta Savage (1892-1962) appeared in the 1939 New York World’s Fair. It is called “Lift Every Voice and Sing, or, The Harp,” and was inspired by James Weldon Johnson and J. Rosamond Johnson’s hymn, “Lift Every Voice:” sometimes called the African American national anthem.

(now the ears of my ears awake and

(now the ears of my ears awake and

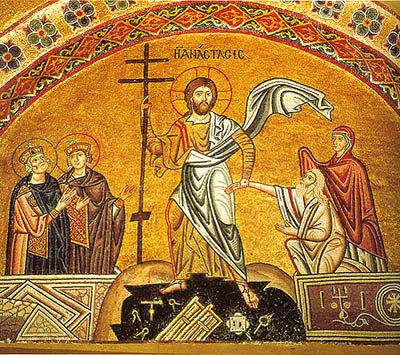

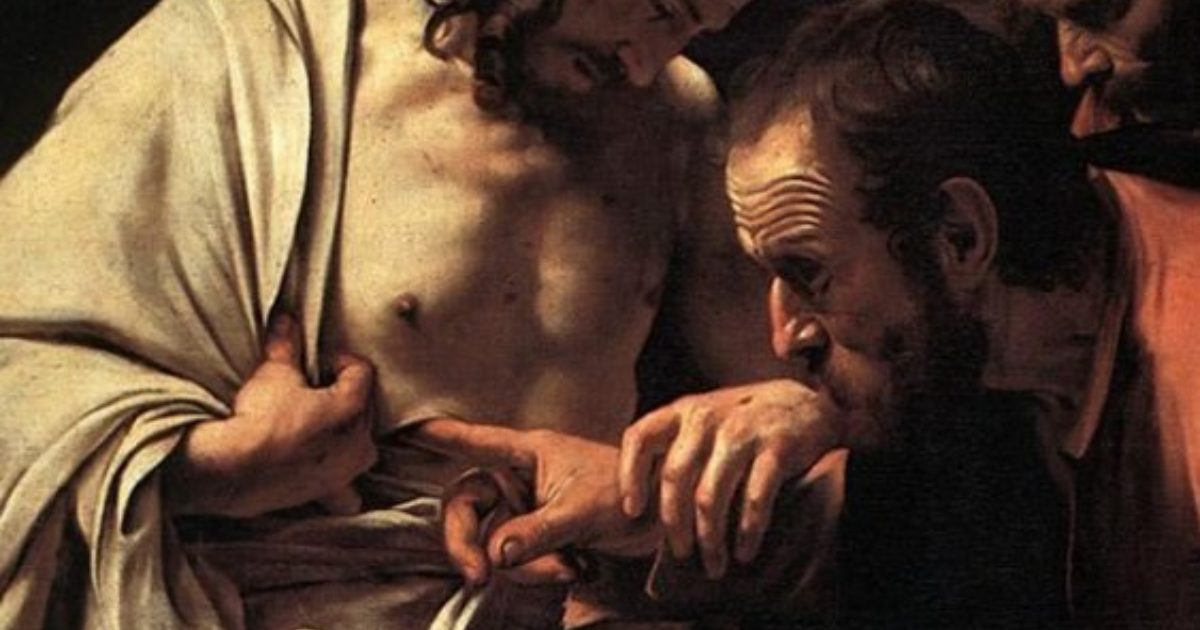

By around the eighth century, this confession was incorporated into the Apostles Creed; most Christians today recite the phrase “He descended into hell” or “He descended to the dead” as part of the Creed (although many

By around the eighth century, this confession was incorporated into the Apostles Creed; most Christians today recite the phrase “He descended into hell” or “He descended to the dead” as part of the Creed (although many

In

In

Patrick embraces a joyful spirituality of nature, wherein a simple herb expresses the mystery of God’s nature, the vibrancy and constancy of wind and water and stone and tree witness to God’s presence and power, and the line between the human world and the animal world, between people and deer, can blur and vanish. This St. Patrick’s Day, may we too seek God first, and so find fulfillment for ourselves and for God’s world.

Patrick embraces a joyful spirituality of nature, wherein a simple herb expresses the mystery of God’s nature, the vibrancy and constancy of wind and water and stone and tree witness to God’s presence and power, and the line between the human world and the animal world, between people and deer, can blur and vanish. This St. Patrick’s Day, may we too seek God first, and so find fulfillment for ourselves and for God’s world.

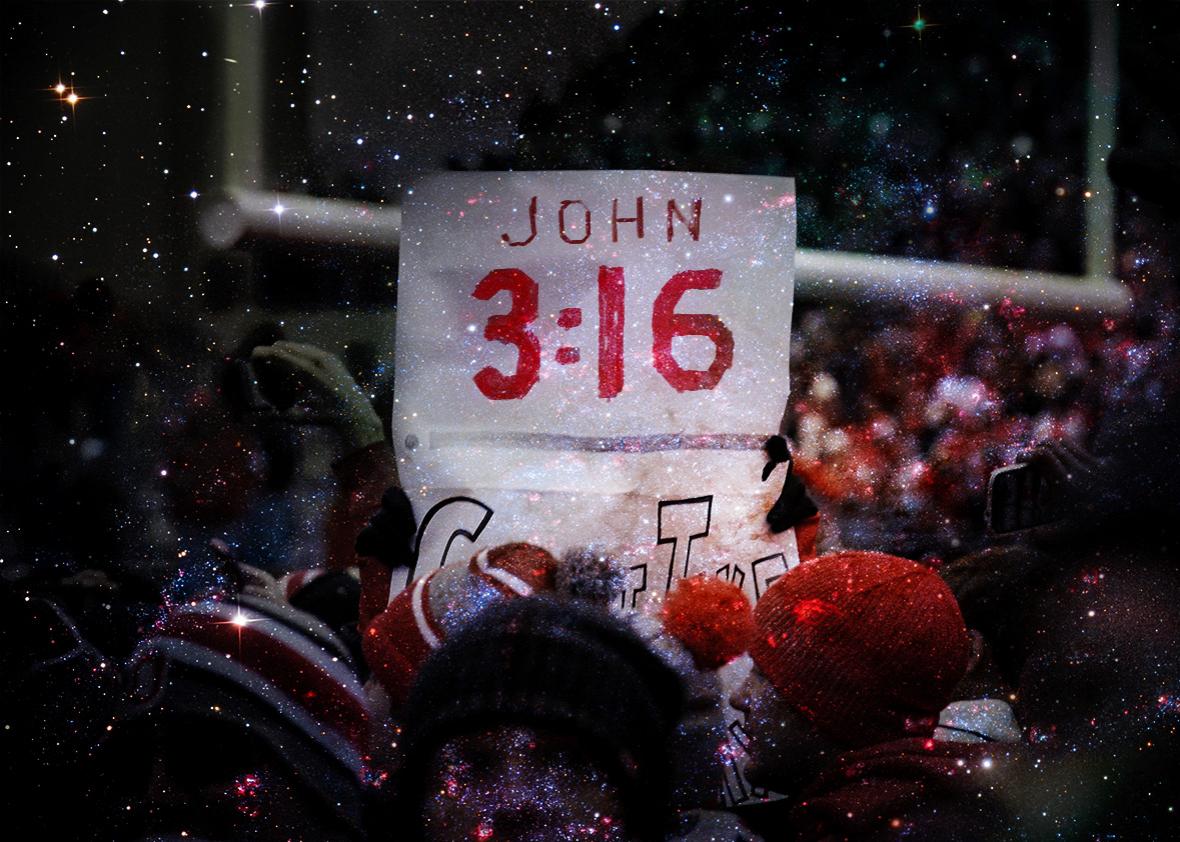

FOREWORD: I am re-sharing this post from 2016, lightly edited, for this Ash Wednesday. The issue it poses has become, if anything, even more urgent today. The recent second impeachment trial for Mr. Trump involved horrific video and witness statements concerning the insurrectionist mob assault on our nation’s capitol January 6. To our sorrow and shame, as the white cross in the center of this image reminds us, that mob contained no small number of

FOREWORD: I am re-sharing this post from 2016, lightly edited, for this Ash Wednesday. The issue it poses has become, if anything, even more urgent today. The recent second impeachment trial for Mr. Trump involved horrific video and witness statements concerning the insurrectionist mob assault on our nation’s capitol January 6. To our sorrow and shame, as the white cross in the center of this image reminds us, that mob contained no small number of