It is now officially Fall: September 23 was the autumnal equinox. Also, nine days ago was Rosh Hashanah, marking the beginning of the High Holy Days and the Jewish New Year. That has always felt right to me. For most of my life I was in school, whether as a student or as a teacher, so even now in retirement, September feels more like the beginning of things than icy January does!

But as Rabbi Jeffrey Salkin writes, the proper Jewish greeting for this season is not “Happy New Year.”

- You can say shanah tovah, “a good year.”

- Some would say: l’shanah tovah.

- You can say l’shanah tovah tikateivu, “may you be inscribed for a good year.”

- You can say: shanah tova u’metukah, “a good, sweet year.”

- You can say, in the period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, and on Yom Kippur itself and beyond, l’shanah tovah tikateivu v’techateimu, “may you be written and sealed for a good year.”

- You can say gmar chatimah tovah, “may you be finished and sealed for a good year.”

- You can say, for the rest of today and tomorrow, heading into and on Yom Kippur, tzom kal, “an easy (and/or meaningful) fast.”

Rabbi Salkin explains, “[O]n the Jewish New Year, there is no mention of ‘happy.’ It’s about goodness. It’s about shanah tovah — a good year.”

Tovah, goodness, is not always the same thing as happy. Tovah, goodness, is mostly about what is meaningful. There is a fundamental difference between wishing that someone have a year of happiness, and the wish that they find meaning.

As I write this, on Monday September 25th, the Days of Awe following Rosh Hashanah have culminated in Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. In Judaism Yom Kippur is a fast day–a day to reflect upon the year past, to repent before God, and to resolve to live faithfully in the year to come.

But the day and its significance as they developed in Jewish life and practice are quite different from the ancient rite for Yom Kippur described in Leviticus 16. The centerpiece of that ancient ritual involved two goats. One was selected by lot as the goat to be offered as “the sin offering” (the most familiar translation of the Hebrew khattat; both the CEB and the NRSVue read “purification offering,” which better catches the significance of this sacrifice in ancient Israel). The second goat was for Azazel. We have no idea what this means! The goat for Azazel was driven out into the wilderness, symbolically carrying away the defilement of the people, so perhaps Azazel was a monster or demon believed to live in waste places; or perhaps Azazel is simply an old word for “wilderness.” The KJV read “scapegoat,” which has entered our language as a person or group blamed for wrongs done by others.

The other goat, selected by lot as belonging to the LORD, is sacrificed. Its blood is taken by the high priest into the inner room of the shrine, called the Most Holy Place, where God was believed to be specially present. This inner chamber held a golden box, called the Ark (the Hebrew word for the Ark, ‘aron, simply means “box,” or “chest”).

The lid of the Ark was a slab of gold, molded in the image of two cherubim: terrible semi-divine heavenly beings like winged sphinxes. The cherubim‘s inner wings overlapped to form a throne: the divine title “the LORD, who is enthroned on the cherubim” (for example, 1 Sam 4:4; Ps 80:1) recalls this connection. The Ark itself served as the LORD’s footstool, making this golden box the intersection of divine and human worlds. In the days of Israel’s wilderness wandering, Moses and Aaron encountered the LORD at the Ark (for example, Exod 25:22).

The lid of the Ark was a slab of gold, molded in the image of two cherubim: terrible semi-divine heavenly beings like winged sphinxes. The cherubim‘s inner wings overlapped to form a throne: the divine title “the LORD, who is enthroned on the cherubim” (for example, 1 Sam 4:4; Ps 80:1) recalls this connection. The Ark itself served as the LORD’s footstool, making this golden box the intersection of divine and human worlds. In the days of Israel’s wilderness wandering, Moses and Aaron encountered the LORD at the Ark (for example, Exod 25:22).

On Yom Kippur, the blood from the people’s purification offerings was applied to the lid of the Ark (kapporet in Hebrew; translated as “mercy seat” in the KJV and the NRSV, but best rendered, as the CEB and NRSVue have it, simply as “cover” or “lid”). This meant that, once a year, the blood of the purification offering was brought to the very feet of God. In ancient Israel, the Day of Atonement was the day when all lingering defilement from the previous year, either accidental or deliberate, was expunged, making full access to and communion with God possible in the new year.

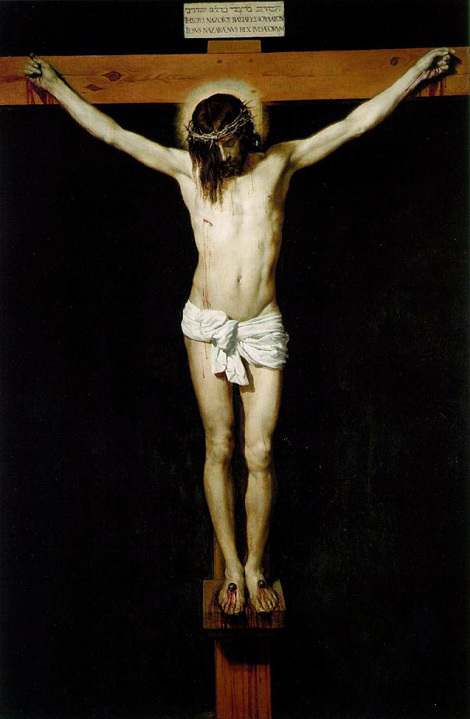

For Christians, the Atonement is a fundamental doctrine, linked mysteriously to the cross. One way to unpack that mystery is to connect Calvary and Yom Kippur, as Paul did in Romans 3:23-25 (NRSVue):

since all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God; they are now justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith.

Many Christians accordingly understand the cross, and the atonement, to mean that Jesus took our place: as our scapegoat and sin offering, he innocently bore our just punishment, and so satisfied God’s justice and assuaged God’s wrath (an interpretation called “Penal Substitution,” developed in particular by Anselm of Canterbury and the Reformer John Calvin).

As a young Christian, this was the only way of understanding the cross I knew: that Jesus had taken on himself God’s wrath, and the deserved punishment for my sin, so that I could be forgiven. I grew up singing “There Is a Fountain Filled With Blood” and “Jesus Paid It All,” although the language of Keith Getty and Stuart Townend’s contemporary hymn “In Christ Alone” may be more familiar today:

In Christ alone, Who took on flesh,

Fullness of God in helpless babe!

This gift of love and righteousness,

Scorned by the ones He came to save.

Till on that cross as Jesus died,

The wrath of God was satisfied;

For ev’ry sin on Him was laid—

Here in the death of Christ I live.

Much as I love this hymn, I cannot sing that bold-faced line anymore. Like many believers, I no longer find this interpretation of the Atonement acceptable. What does it say about God, if God’s wrath can only be assuaged by blood, even the blood of his innocent Son? Focusing solely on the death of Jesus makes his life, and his teaching, irrelevant. This certainly does not mean that I no longer believe in the atonement! But I am persuaded that both the origins of our English word “atonement” and the biblical texts relating to Yom Kippur point us in another direction.

I had long found in the word “atone” an intriguing and deeply satisfying pun–the word can also be read as “at one.” That, I thought, is surely the result of Christ’s atonement on the cross: God’s wrath satisfied, our guilt paid for, we can now enjoy communion with the Divine. However, I have since learned that this apparent pun is actually how the word “atonement” came about!

The Oxford English Dictionary dates “atonement” to the early 16th century, when it was coined out of the phrase “at one”–influenced by the Latin adunamentum (“unity”), and an older word, “onement” (from an obsolete verb form, “to one,” meaning “to unite”). Sadly, as modern English dictionaries make clear, “to atone” has come to mean “to make amends, restitution, or reparation.” But the then freshly-minted word was used instead to talk about reconciliation: specifically, the reconciliation of God and humanity accomplished by Christ.

When the King James Version of the Bible was translated in 1611, the relatively new expression “make atonement” was used to translate the Hebrew verb kipper, particularly in connection with Yom Kippur. This Hebrew term originally meant “cover,” but kipper came to be used specifically for cleansing and purification–not, note, for punishment or payment. Certainly, nothing in Leviticus 16 suggests this: the goat for Azazel, note, is not killed, and is not called a sacrifice.

In Romans 3:25, the Greek word translated “sacrifice of atonement” in the NRSV (the KJV has “propitiation”) is hilasterion. But in the Greek translation of Jewish Scripture, the Septuagint, hilasterion refers neither to the sin offering nor the scapegoat, but to the lid of the Ark: the kapporet. The CEB translation of hilasterion in Rom 3:25 (see also the footnote in the NRSVue) as “place of sacrifice” is a little better, though still misleading. Paul’s point appears to be that the cross where Jesus’ blood was spilled has become the kapporet: the point where divine and human worlds intersect, and so the place where reconciliation–atonement–happens. The Common English Bible, which translates Yom Kippur as “Day of Reconciliation,” nicely captures the original meanings of both the English word “atonement” and the Hebrew rite of Yom Kippur.

In Philippians 2:1-13, the epistle for this Sunday, Paul quotes a hymn of the earliest church:

Though he was in the form of God,

he did not consider being equal with God something to exploit.

But he emptied himself

by taking the form of a slave

and by becoming like human beings.

When he found himself in the form of a human,

he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death,

even death on a cross.

Therefore, God highly honored him

and gave him a name above all names,

so that at the name of Jesus everyone

in heaven, on earth, and under the earth might bow

and every tongue confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

In this hymn, Jesus is neither a scapegoat nor a sin offering. He is not our replacement, but our representative. Being at once God and Human, he overcomes in his own Person the gap between humanity and divinity. But of course, being fully and truly human means being finite: like us, Jesus was born, lived, learned, grew, suffered, and died. But the specific death Jesus died–that he indeed chose to die–placed him with the shamed and outcast; the scorned and unjustly persecuted. As Immanuel, God with us (Matt 1:22-23), Jesus proves God’s presence with us even in the midst of pain, abandonment, and death itself.

Elsewhere the apostle Paul puts it this way:

If we were reconciled to God through the death of his Son while we were still enemies, now that we have been reconciled, how much more certain is it that we will be saved by his life? And not only that: we even take pride in God through our Lord Jesus Christ, the one through whom we now have a restored relationship with God (Romans 5:6-11).

In Christ’s death, the gap between humanity and divinity is bridged: we are reconciled (Greek katalasso) to God. In Christ’s resurrection, we are given the hope and the promise of our own deliverance from death. By entering into our life, and even into our death, Jesus draws God near to us, and us near to God. He brings God’s divinity down to where we are, and lifts our humanity up to where God is.

Regarding the Atonement (and that Getty and Townend hymn!) New Testament scholar N. T. Wright observes,

We must of course acknowledge that many, alas, have offered caricatures of the biblical theology of the cross. It is all too possible to take elements from the biblical witness and present them within a controlling narrative gleaned from somewhere else, like a child doing a follow-the-dots puzzle without paying attention to the numbers and producing a dog instead of a rabbit. This is what happens when people present over-simple stories, as the mediaeval church often did, followed by many since, with an angry God and a loving Jesus, with a God who demands blood and doesn’t much mind whose it is as long as it’s innocent. You’d have thought people would notice that this flies in the face of John’s and Paul’s deep-rooted theology of the love of the triune God: not ‘God was so angry with the world that he gave us his son’ but ‘God so loved the world that he gave us his son’. That’s why, when I sing that interesting recent song and we come to the line, ‘And on the cross, as Jesus died, the wrath of God was satisfied’, I believe it’s more deeply true to sing ‘the love of God was satisfied’, and I commend that alteration to those of you who sing that song, which is in other respects one of the very few really solid recent additions to our repertoire.

L’shanah tovah, friends. A good, and meaningful, year to you and yours, in which you experience daily the power and presence of God.