Outside the headquarters of the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Alabama stands this monument to the martyrs of the civil rights movement, whose names are carved into the fountain at its center. On the wall around this centerpiece is engraved, “. . .until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream. Martin Luther King, Jr.”

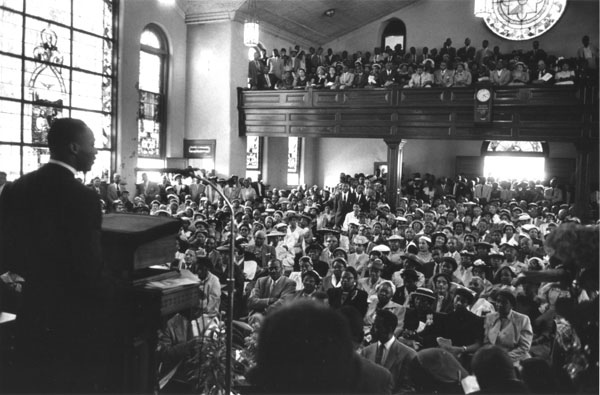

The attribution of the quote is correct: this exact wording comes from Dr. King’s “I Have A Dream” speech, delivered on August 28, 1963 at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington D.C., during the March on Washington: one of the most famous speeches of modern times:

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their self-hood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: “For Whites Only.” We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until “justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

But Dr. King, a Baptist preacher, certainly knew that when he said those words, he was paraphrasing the words of the prophet Amos:

I hate, I reject your festivals;

I don’t enjoy your joyous assemblies.

If you bring me your entirely burned offerings and gifts of food

I won’t be pleased;

I won’t even look at your offerings of well-fed animals.

Take away the noise of your songs;

I won’t listen to the melody of your harps.

But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream (Amos 5:21-24)

This was not the first time that Dr. King cited this passage from Amos. Indeed, he cited this passage earlier that very year, in April, in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”:

I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channeled into the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action. And now this approach is being termed extremist. But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.” Was not Amos an extremist for justice: “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever flowing stream.” Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel: “I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” Was not Martin Luther an extremist: “Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise, so help me God.” And John Bunyan: “I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a butchery of my conscience.” And Abraham Lincoln: “This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.” And Thomas Jefferson: “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal . . .” So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? In that dramatic scene on Calvary’s hill three men were crucified. We must never forget that all three were crucified for the same crime–the crime of extremism. Two were extremists for immorality, and thus fell below their environment. The other, Jesus Christ, was an extremist for love, truth and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment. Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists. From “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dr. King was in jail, in Birmingham, for leading sit-ins, marches, and protests of racial discrimination in that city. While in jail, he learned of an open letter published in Birmingham area papers, called “A Call for Unity”—signed by eight prominent white Alabama clergymen (including two Methodist bishops). The letter bemoans a “series of demonstrations by some of our Negro citizens, directed and led in part by outsiders,” and says, “We… strongly urge our own Negro community to withdraw support from these demonstrations, and to unite locally in working peacefully for a better Birmingham. When rights are consistently denied, a cause should be pressed in the courts and in negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets.”

In his book Why We Can’t Wait, Dr. King remembered writing his response to this open letter: “Begun on the margins of the newspaper in which the statement appeared while I was in jail, the letter was continued on scraps of writing paper supplied by a friendly black trusty, and concluded on a pad my attorneys were eventually permitted to leave me.” The letter was published in June 1963 in three magazines, including Christian Century; but it was in the July issue of Atlantic Monthly that it reached its largest audience. It has since been reprinted countless times–but it takes some looking to find “A Call for Unity”!

Those eight white Alabama clergymen who disapproved of Dr. King felt that civil disobedience is inappropriate for Christians. Evidently, Christians should express their faith in church, where it belongs. Oddly, we still sometimes think of social justice and Spirit-filled worship as two different things–indeed, we may go so far as to describe these as the concerns of different churches. But for Amos, there was no separating the two.

The passage from Amos cited by Dr. King powerfully expresses God’s passion for justice, and God’s rejection of any form of religion that does not issue forth in lives of justice. Without right living, our prayers and hymns are just noise. And lest we think that this is just Amos’ view, or just the Old Testament’s view, the New Testament also proclaims this truth:

If anyone says, I love God, and hates a brother or sister, he is a liar, because the person who doesn’t love a brother or sister who can be seen can’t love God, who can’t be seen (1 John 4:20).

Without justice, right worship is impossible. However, I am also persuaded that right living is impossible without right worship–or at least, very, very difficult! If we seek to establish God’s justice on our own steam, we will burn out quickly. That’s why Jesus named two great commandments: love God, and love neighbor (Matthew 22:34-40; Mark 12:28-34; and Luke 10:25-28). Just as love for the neighbor shows forth our love for God, so it is as we love God, and know ourselves loved by God in our worship, that we are empowered to love our neighbor.

While those eight prominent white Alabama clergymen may have disapproved of Dr. King, Amos would have heartily approved! Amos condemned the wealthy of his own day, declaring that God’s judgment would fall upon Israel for their callousness to the forgotten poor:

because they have sold the innocent for silver,

and those in need for a pair of sandals.

They crush the head of the poor into the dust of the earth,

and push the afflicted out of the way (Amos 2:6-7).

Amos confronted both the religious and the political leaders of his own day for their involvement in injustice. Amaziah, high priest at Bethel, condemned Amos as an outside agitator (!) from the southern kingdom of Judah, and ordered him to go back home:

You who see things, go, run away to the land of Judah, eat your bread there, and prophesy there; but never again prophesy at Bethel, for it is the king’s holy place and his royal house (Amos 7:12-13).

Amos would have been delighted by Dr. King’s response to the charge that he too was an “outsider.” In his “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” he wrote,

I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.

Was Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. a prophet, like Amos? That is not an easy question for an Old Testament scholar to answer! After all, the prophets of ancient Israel believed that the words that they bore were God’s words, not their own: that is why Amos, like other prophets in Israel, speaks in God’s name and with God’s voice, in the first person (“I hate, I reject your festivals. . . If you bring me your entirely burned offerings and gifts of food I won’t be pleased”), as God’s spokesperson. Dr. King certainly never claimed such an exalted status for himself, or for his words.

But the prophets were also ministers of God’s justice, shaking Israel out of its complacency and calling their people to remember who they were, and live as God’s people. As a voice raised on behalf of the oppressed, as a tireless laborer in the cause of God’s justice, as an example of what one person devoted to God’s call can accomplish—Dr. King was a prophetic witness to his own time, and to ours.

Today, when the gap between rich and poor has become greater than at any time since the Gilded Age and the robber barons; today, when the Southern Poverty Law Center records 1,094 reports of harassment and intimidation in the month after our recent election, “more than the group would usually see over a six-month period; ” today, when the continually rising tide of deaths of young African American men by police violence makes Dr. King’s dream seem more and more remote, may we recommit ourselves to work for and pray for the day when “justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

AFTERWORD: Thank you to former student and colleague in ministry Rev. Chad Bogdewic, who invited me to preach the sermon on which this blog is based at a service honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at First UMC in Ellwood City, PA; to Rev. Angelique Bradford, pastor at Ellwood City First, for hosting this event, and to the Ellwood City Ministerium, for planning it.

Jesus’ baptism prefigures his death and burial, while we who follow him are baptized “into his death”–dying to self and sin. Similarly the author of 1 Peter saw the waters of baptism in terms of death and destruction:

Jesus’ baptism prefigures his death and burial, while we who follow him are baptized “into his death”–dying to self and sin. Similarly the author of 1 Peter saw the waters of baptism in terms of death and destruction:

Having grown up in a non-liturgical church (I don’t believe I knew about the seasons of the church year, apart from Easter and Christmas, until college), I always wondered why, in some traditions, the candle for the third Sunday of Advent is pink, not purple. I always assumed that it had something to do with the veneration of Mary–but, as happens far more often than I care to admit, I was wrong.

Having grown up in a non-liturgical church (I don’t believe I knew about the seasons of the church year, apart from Easter and Christmas, until college), I always wondered why, in some traditions, the candle for the third Sunday of Advent is pink, not purple. I always assumed that it had something to do with the veneration of Mary–but, as happens far more often than I care to admit, I was wrong. The website “

The website “