Tuesday, November 19th was the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, perhaps the most important speech in American history.

Lincoln delivered his address as part of a ceremony to dedicate the Civil War battlefield at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania as a national cemetery, although as he famously said,

in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.

Those men, from the north and from the south, who fought and died at Gettysburg did not do so as part of anyone’s grand strategic design. No one had intended to fight a battle at Gettysburg. The armies of George Meade and Robert E. Lee chanced to meet there, however, on July 1, 1863, and so the battle was joined.

After two days of bitter fighting, the Federal troops were in control of the high ground. Lee sent George Pickett, with some 15,000 men, in a desperate charge against Winfield Scott Hancock’s troops, entrenched on Cemetery Ridge–though James Longstreet and others on his staff warned that the charge could not succeed.

As Lee had been warned that it would, the attack failed utterly: Pickett’s charge was repulsed, with terrible casualties–two-thirds of his division were killed.

When Lee ordered Pickett to rally his division as a rear guard against the Union troops “should they follow up their advantage,” Pickett tearfully responded, “General Lee, I have no division now” (Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative, Vol 2, Fredricksburg to Meridian [New York: Random House, 1986], 568). The battle was over, the Union had gained a much-needed victory, and though the war would drag on for another two years, the Confederate cause was lost.

So, what does any of this have to do with Genesis 3? The connection lies in General Robert E. Lee’s response to this catastrophe.

Lee said immediately to Pickett, “This has been my fight, and upon my shoulders rests the blame. . . . Your men have done all that men can do. The fault is entirely my own.” As Lee rode about the battlefield, ordering his troops for retreat, he said it again and again: “It’s all my fault.” “The blame is mine.” “All this has been my fault. It is I who have lost this fight, and you must help me out of it the best way you can.” (Foote, Civil War 2, 568)

Lee’s words are so striking precisely because they are so rare. Sadly, we are far more accustomed to hearing folk refuse to shoulder blame or to take responsibility for their actions, whether on the national news, in our communities, or in our own homes.

The second Genesis creation story, as we have seen, is an etiological narrative, aiming to explain the world we see around us by reference to its beginnings. So it is little wonder that in Genesis 3:12-13, when God asks if the woman and the man have eaten the fruit of the tree of knowledge, instead of owning up to the fact, they try to pass the blame one to someone else.

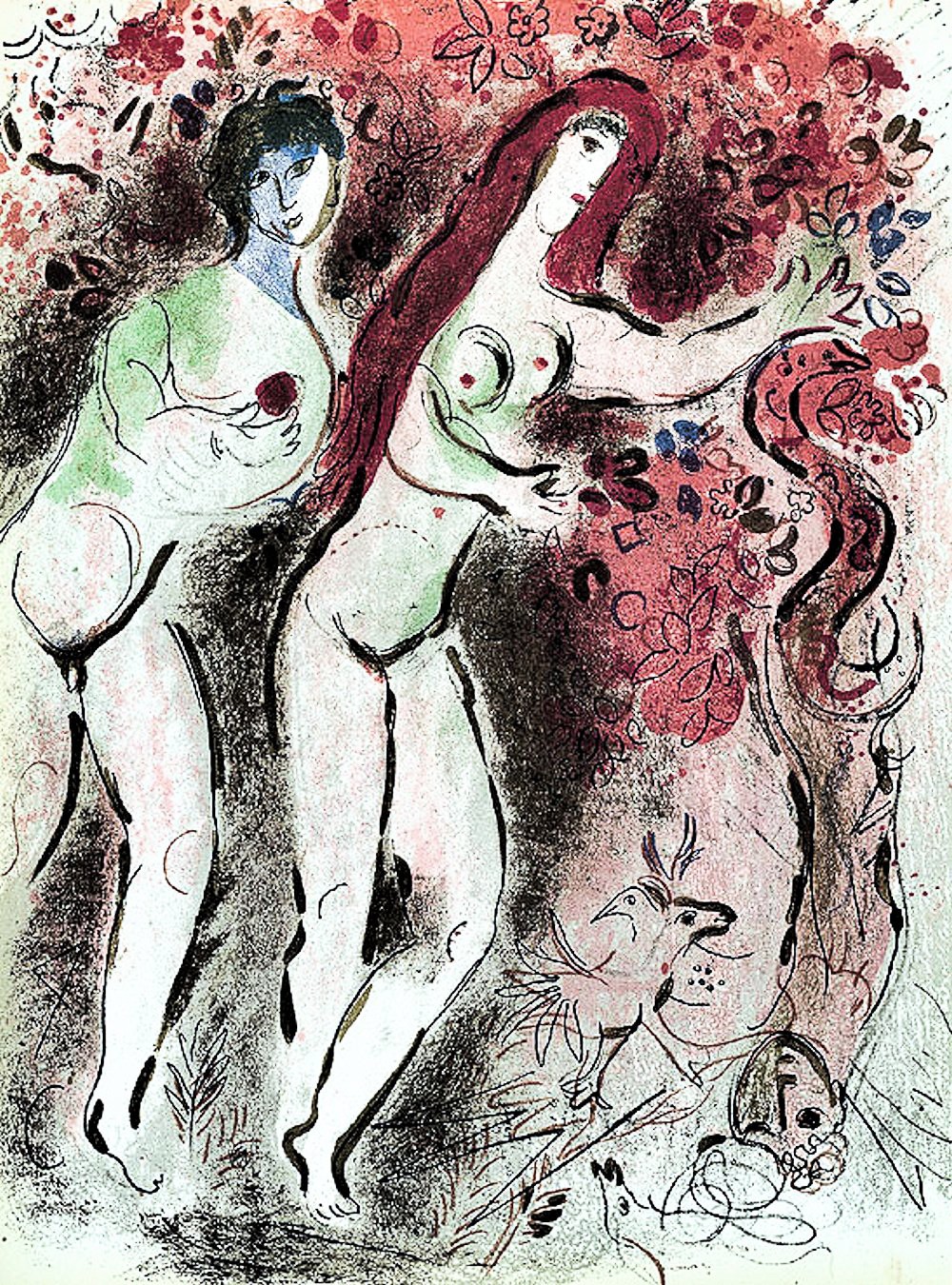

The man declares, “The woman you gave me, she gave me some fruit from the tree, and I ate” (Gen 3:12). So, he not only blames Eve, but God, who had brought her to him! Some later traditions accept this argument, and place the blame for sin–the human condition of estrangement from God, the world, and one another–upon the woman.

The woman in turn blames the snake: “The snake tricked me, and I ate” (Gen 3:13).

God, however, buys none of this. No one in this story succeeds in passing the buck! As the narrative unfolds in Genesis 3:14-19, God holds each character accountable, and each character suffers the consequences of choices made.

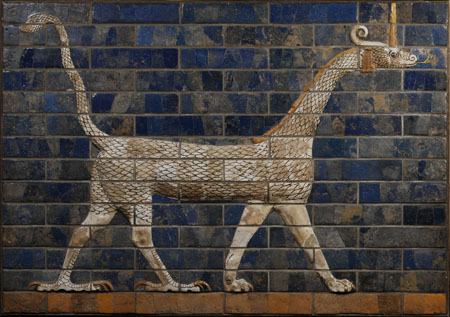

First come the consequences for the snake. Described when we first encounter it as “the most intelligent of all the wild animals that the LORD God had made” (Gen 3:1), the snake is now

cursed

out of all the farm animals,

out of all the wild animals (Gen 3:14)

The curse on the snake comes in two parts. First, it loses its limbs, and its ability to speak:

On your belly you will crawl,

and dust you will eat

every day of your life (Gen 3:14).

Once again, etiological features of this story come to the fore. Why don’t snakes have legs? Why do they crawl on their bellies? Why do they keep sticking out their tongues and licking the ground? The short answer, in this ancient story, is that snakes are cursed. Because of their involvement in humanity’s disobedience, they must crawl on the ground and continually lick the dust–which is also why snakes no longer talk.

The second aspect of the curse turns to another etiological feature: why do snakes bite? Why are they poisonous? Why do we hate and fear them? The LORD God declares,

I will put contempt

between you and the woman,

between your offspring and hers.

They will strike your head,

but you will strike at their heels (Gen 3:15).

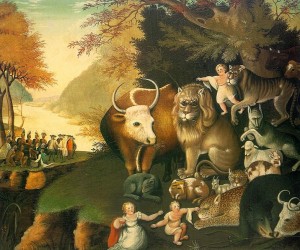

In Genesis 3, notice, the snake is just a snake. True, it doesn’t start out like the snakes that we know, but the narrative explains how that change happened. From the first, the snake is introduced as one of the animals God has made–the most clever among them, yes, but still an animal. The curse reiterates this: among all the animals that the LORD has made, both wild and domestic, the snake is now the lowest–the most cursed.

Later tradition identifies the snake in the garden with Satan. But the text itself explicitly does not do that. Further, some Christian interpretations regard Genesis 3:15 as a prediction of the coming of Christ: the Devil will strike at his heel, wounding him on the cross, but Christ with his resurrection and at his return will crush the enemy’s head. But this too is nowhere in the text before us. As Reformer John Calvin observed in his commentary on this passage,

other interpreters take the seed for Christ, without controversy; as if it were said, that some one would arise from the seed of the woman who should wound the serpent’s head. Gladly would I give my suffrage in support of their opinion, but that I regard the word seed as too violently distorted by them; for who will concede that a collective noun is to be understood of one man only? Further, as the perpetuity of the contest is noted, so victory is promised to the human race through a continual succession of ages. I explain, therefore, the seed to mean the posterity of the woman generally.

Genesis 3 is not science. Herpetologists are happy to explain to us that snakes sense the presence of prey or enemies in large part by “tasting” the air and the ground–that is why they stick out their tongues. They will also assure us of the importance of snakes as predators in the ecosystem, and tell us that while we should be respectful of any wild animal, most snakes are neither venomous nor aggressive.

Genesis 3 isn’t history, either. This is not the account of how sin entered the world, to be passed down ever since through the human bloodline like blue eyes or a predisposition to schizophrenia. This is a narrative describing what human beings are like, and setting forth the consequences of our choices for ourselves and for our world. In the story world of Genesis, the woman and the man alike attempt to pass the buck, refusing to accept blame or responsibility. But the buck proves to be unpassable! God holds every character in the narrative accountable.

For the woman, the consequence of her accountability is suffering:

I will make your pregnancy very painful;

in pain you will bear children.

You will desire your husband,

but he will rule over you (Gen 3:16).

This is the first mention anywhere in these creation accounts of the subordination of women to men. Notice, though, that it is presented not as God’s intention, but as a consequence of human rebellion.

Just as the woman suffers in bringing forth life from her womb, so in this story the man suffers in wresting life out of the ground:

cursed is the fertile land because of you;

in pain you will eat from it

every day of your life.

Weeds and thistles will grow for you,

even as you eat the field’s plants;

by the sweat of your face you will eat bread—

until you return to the fertile land,

since from it you were taken;

you are soil,

to the soil you will return (Gen 3:17-19).

Again, these are etiological features of the story: why is childbirth so difficult and dangerous? Why are there thorns and thistles and weeds? Why is life so hard?

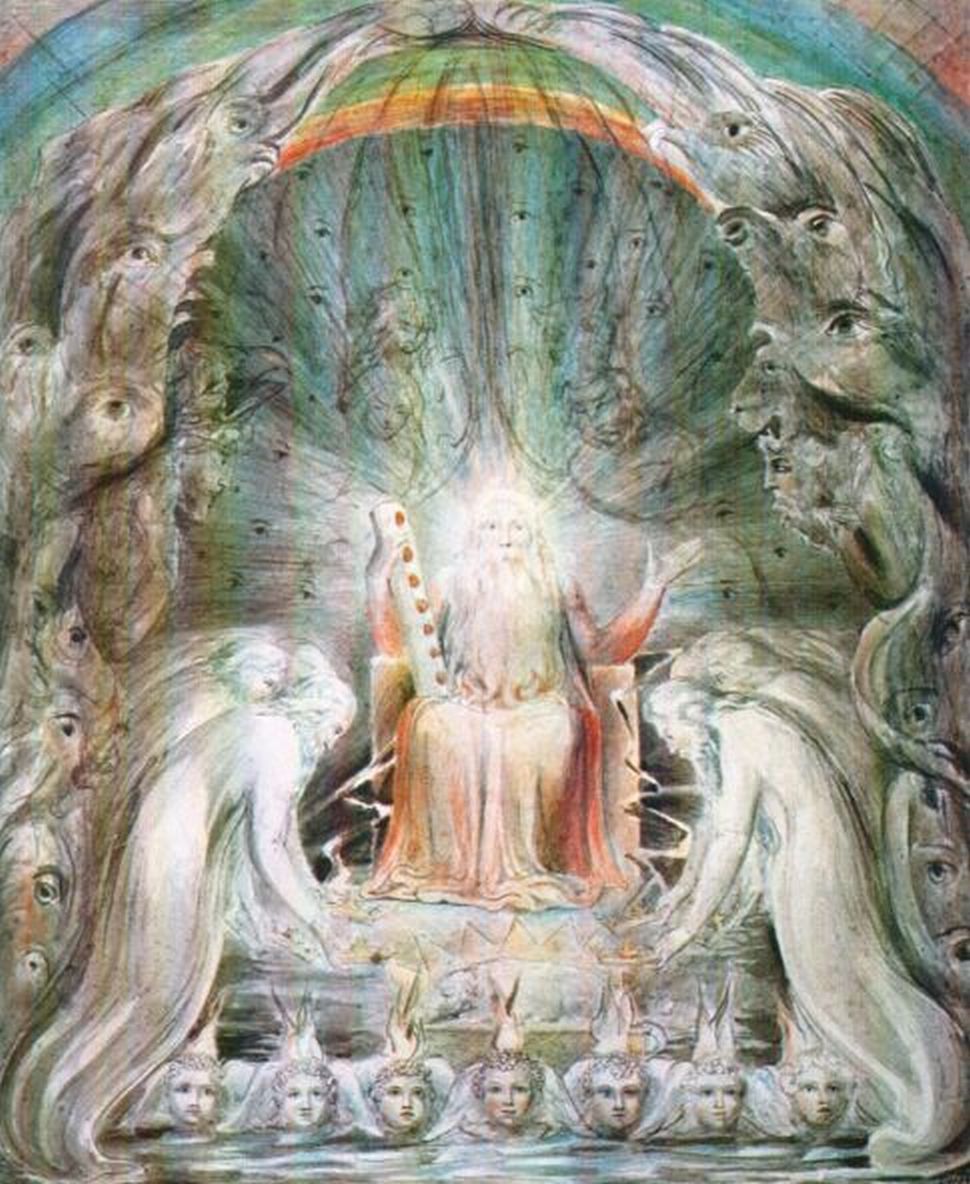

But finally, the biggest question is also the hardest one: why do we die? As we saw last week, in the garden the woman and man have access to the Tree of Life: they need never die. But now,

the Lord God sent him out of the garden of Eden to farm the fertile land from which he was taken. He drove out the human. To the east of the garden of Eden, he stationed winged creatures wielding flaming swords to guard the way to the tree of life (Gen 3:23).

Without access to the life-giving fruit of the tree, women and men will now die–just as God had said they would, should they eat from the forbidden tree of knowledge. Next time, we will think about what the significance of that action might be. But for now, we will focus on the consequences of this act.

Leaving the garden of Eden behind, the woman and the man now enter a world like the world that we know, where life can be brutal and hard, where pain and suffering are sad realities, and where all of us must, sooner or later, die.

But unlike the snake, the woman and the man are not cursed! The ground is cursed, but they are not. Indeed, God cares for them, covering their nakedness with garments God makes from the skins of animals (Gen 3:21). In the end, this story is about God’s desire to be in relationship with us even when we spurn that relationship. We are not cursed, spurned, or rejected by God, even though the consequences of our actions wound our world and one another.

The season of Advent is nearly upon us, when we celebrate the promise of Christ’s coming. In Jesus, God takes on our very being, and offers us God’s own; in Christ, we share in the Divine life!

No less than Adam, or Eve, or even the snake, we must take responsibility for our own actions: the buck stops here. But Jesus has come to take that burden, and to give us a new heart, a new life: indeed, to take us into a new creation, in which all things are become new (2 Cor 5:17).

AFTERWORD

The Bible Guy wishes all and sundry a very Happy Thanksgiving! I am off to the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature and then to spend the holiday with family; this blog will resume in December.

Now, the LORD God permits t

Now, the LORD God permits t

But in Genesis 1:26, the priests of Israel say that God’s likeness is seen in humanity, and implicitly (since that likeness is shown in “male and female”), in relationships.

But in Genesis 1:26, the priests of Israel say that God’s likeness is seen in humanity, and implicitly (since that likeness is shown in “male and female”), in relationships.

As long as I believe in an enchanted world, a world haunted by gods and demons in which every rock, stone or tree is possessed by a spirit, I can neither formulate laws to render the behavior of my world meaningful, nor make predictions based on those laws. The interaction of objects in the world will be due to the capricious decisions that those various spirits might make in their interactions with one another.

As long as I believe in an enchanted world, a world haunted by gods and demons in which every rock, stone or tree is possessed by a spirit, I can neither formulate laws to render the behavior of my world meaningful, nor make predictions based on those laws. The interaction of objects in the world will be due to the capricious decisions that those various spirits might make in their interactions with one another.