This Sunday, the last Sunday after Pentecost, marks the end of the Christian year; next Sunday, with Advent, a new year begins. The last day of the Christian year is called the Reign of Christ, or the feast of Christ the King. The Gospel reading for the day is Matthew 25:31-46, Jesus’ famous parable of the last judgment, when the Son of Man judges the world:

All the nations will be gathered in front of him. He will separate them from each other, just as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats (Matt 25:32).

We often think of the shepherd as a humble, comforting image, expressing nurture and care. But the metaphor of the king as shepherd was common in the ancient Near East and is very old, going back to the ancient Sumerian king lists. Hammurabi, founder of the first great Babylonian empire in the eighteenth century BCE, had written, “Hammurabi, the shepherd, called by Enlil am I; the one who makes affluence and plenty abound.” The title was used by the Assyrian kings as well: Adad-nirari III (810–723 BCE) is described as “(a king) whose shepherding they [i.e., the gods] made as agreeable to the people of Assyria as (is the smell of ) the Plant of Life,” and Esarhaddon (680–669 BCE) is called “the true shepherd, favorite of the gods.” The expression was still in use at the rise of the Neo-Babylonian Empire—both Nabopolassar (626–605 BCE) and Nebuchadnezzar (605–562 BCE) were called “shepherds.”

The Hebrew Bible amply attests to the use of the shepherd metaphor for Israel’s rulers (for example, 2 Sam 5:2; Jer 3:15; Ezek 34:1-10; Mic 5:1-5a; Zech 10:2-3). By analogy, the LORD as king of the universe is also called a shepherd (see Ps 23; Ezek 34:11-16), an idea that lies back of the New Testament image of Jesus as the Good Shepherd in John 10, as well as here in Matthew 25. But the specific source back of Matthew’s judgment scene is the lesson from the Hebrew Bible for Sunday, Ezekiel 34:11-16, 20-24.

This prophetic text from the Babylonian exile is reminiscent of the far better-known Psalm 23. Here as there, the LORD causes the flock to lie down in good pasture, beside streams of waters. But the mention of the settlements in the land (“inhabited places” in the CEB; 34:13) breaks up this pastoral imagery to remind the reader that this is about Israel after all, not about sheep: God will bring the exiles home, and repopulate desolated Judah.

The last verse of this section begins as a summary of 34:11-16, reiterating God’s determination to seek out and care for the scattered sheep. But then, abruptly, the image shifts: “I will seek out the lost, bring back the strays, bind up the wounded, and strengthen the weak. But the fat and the strong I will destroy” (34:16). This statement, like the mention of settlements in 34:13, explodes the metaphor: it makes no sense for any shepherd to destroy the strong and healthy sheep!

No wonder the Greek Septuagint (LXX), the Syriac, and the Vulgate all read “I will watch over” instead, assuming an original Hebrew ‘eshmor instead of ‘ashmid (“I will destroy”). The two words are nearly identical in Hebrew, where vowels are not written, and the consonants d and r look a great deal alike. It is easy to understand a scribe mistaking one for the other. The reading followed by the LXX certainly seems a better fit with the context of 34:11-16, which stresses God’s care for the flock, in striking contrast to the cruelty of the false shepherds: that is, Israel’s kings. Numerous commentators on Ezekiel (for example, Walther Zimmerli, Ezekiel 2, 208; Daniel Block, Ezekiel 25—48, 287; Leslie Allen, Ezekiel 20—48, 157) therefore follow the LXX here.

On the other hand, not only the CEB, but also NIV, NRSV, and even the KJV all stay with the Hebrew Bible here, which reads ‘ashmid (“I will destroy”)– and they are right to do so. The next phrase in Ezekiel 34:16 makes the prophet’s meaning clear: “But the fat and the strong I will destroy, because I will tend my sheep with justice.” God’s justice was seen in 34:1-10 with the punishment of the false shepherds, Israel’s past kings. But while the shepherds had certainly been guilty, the sheep are not therefore innocent! Throughout this book, Ezekiel rejects the exilic community’s claim that they are innocent victims (see, for example, 18:1-4).

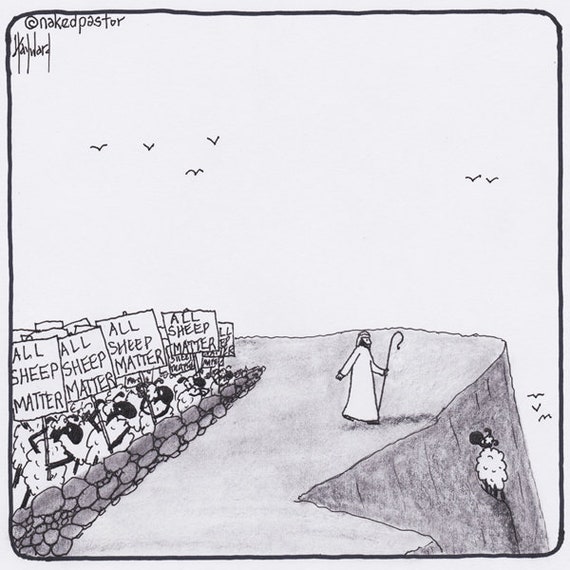

In the next section, 34:17-24, God’s justice is visited on the sheep, just as it had been visited on the shepherds. Once more good theology trumps good animal husbandry, as God sides with the weak and injured over against the fat and strong (Christian readers may be reminded of the shepherd who leaves the ninety-nine unguarded in the fold to seek out the one lost lamb; Matt 18:10-14//Luke 15:3-7)! The startling introduction of this idea in 34:16 is in keeping with Ezekiel’s style elsewhere: this prophet loves to shock his audience.

God’s judgment upon the flock falls into two parts, the accusation (34:17-19, unaccountably left out of the lectionary reading), and the pronouncement of judgment (34:20-24). The accusation opens, “As for you, my flock, the Lord God proclaims: I will judge between the rams and the bucks among the sheep and the goats” (34:17)–words that directly call to mind the judgment scene in Matthew 25 (compare 25:32).

In Matthew as in Ezekiel, the basis of the judgment is regard for the least (Matt 25:40, 45). So, in Ezekiel, the strong sheep are taken to task for selfishly and greedily trampling the pasture and muddying the water so that others cannot eat or drink (34:18-19). The point is expanded in 34:21: the strong are condemned for thrusting the weak aside.

In our own day, the gap between rich and poor is wider than it has ever been, as the lion’s share of the world’s resources is claimed by a diminishing minority of its people. The trampling of our earth and fouling of our water, through irresponsible use of this world’s resources, now threatens the entire planet through climate change, even as it robs opportunity from the most vulnerable. Ezekiel plainly states God’s place in this: on the side of the poor, and on the side of the abused land. God declares, “I will rescue my flock so that they will never again be prey” (34:22). Perhaps, friends, before piously invoking Psalm 23, we should remember what kind of shepherd our LORD is, and what being faithful members of his flock may ask of us. The image may prove not so much comforting as challenging.