Want to hear a good ghost story? You can’t beat Ezekiel 37:1-14, the Hebrew Bible reading for Pentecost Sunday. If you have never heard this one before, you are likely to wonder, “What is this doing in the Bible?” It is a scene out of a horror movie, or a Stephen King novel.

First, the prophet is taken in a vision by the hand of the Lord to a valley: an abandoned battlefield, filled with dry, dusty, disjointed bones.

God asks Ezekiel, “Human one, can these bones live again?” (37:3). The obvious answer is no—there is no life, and no possibility of life, in this place! The bodies strewn across the valley are not only dead, they are long dead (37:2). But since his call, Ezekiel has seen (see 1—3) and done (see 4—5; 12:1-20; 24:15-27; as well as 37:15-28) some very odd things in the Lord’s service. So he answers, simply “Lord God, only you know” (37:3).

God asks Ezekiel, “Human one, can these bones live again?” (37:3). The obvious answer is no—there is no life, and no possibility of life, in this place! The bodies strewn across the valley are not only dead, they are long dead (37:2). But since his call, Ezekiel has seen (see 1—3) and done (see 4—5; 12:1-20; 24:15-27; as well as 37:15-28) some very odd things in the Lord’s service. So he answers, simply “Lord God, only you know” (37:3).

Now, God commands the prophet, “Prophesy over these bones, and say to them, Dry bones, hear the Lord’s word!” (37:4). As Ezekiel delivers God’s promise of life to the dead bones, he hears “a noise, a rattling, and the bones came together, bone to its bone” (37:7, NRSV). He watches as, in accordance with the word he had proclaimed (37:5), the bones are joined by tendons and covered over with flesh. Now, instead of a valley full of dry bones, the prophet is standing in a valley filled with corpses.

Again God speaks: “Prophesy to the breath; prophesy, human one! Say to the breath, The Lord God proclaims: Come from the four winds, breath! Breathe into these dead bodies and let them live” (37:9).

Again God speaks: “Prophesy to the breath; prophesy, human one! Say to the breath, The Lord God proclaims: Come from the four winds, breath! Breathe into these dead bodies and let them live” (37:9).

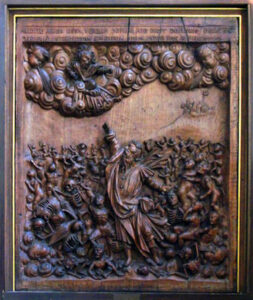

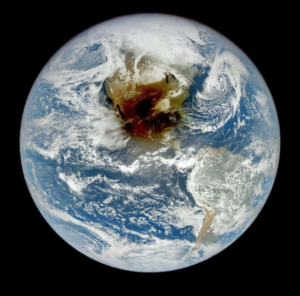

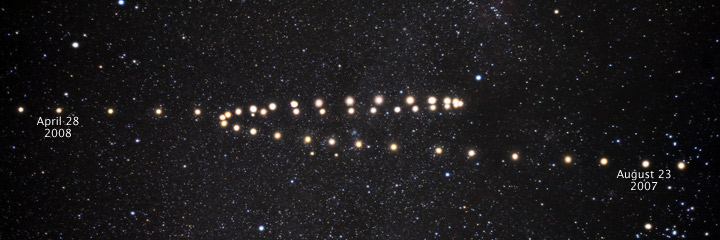

Hebrew writers love puns. A pun on the different meanings of the Hebrew word ruakh (“breath” in the 37:8-9) runs through this story. First, this word can mean “breath:” so, to say that there was no ruakh in the bodies (37:8) simply means that they were not breathing. Related to this meaning is the use of ruakh for “wind” (37:9). In keeping with the invisible force of the wind and the life-giving power of the breath is a third meaning. Ruakh can be rendered as “spirit”—that is, the empowering, enlivening agency of people, and of God (more on that one shortly). So, as Ezekiel prophesied to the wind (ruakh), breath (ruakh) entered the bodies, and “they came to life and stood on their feet, an extraordinarily large company” (37:10)–not, please note, this

but this:

What does this vision mean? In 37:11-14, God explains. The dry bones are Ezekiel’s community, the house of Israel: exiled, and in despair. They say, “Our bones are dried up, and our hope has perished. We are completely finished.” (37:11)–and they are right! Jerusalem is destroyed, the king is in chains, the temple is gone, and the people are scattered, in hiding or in exile.

But, deliverance is promised–a resurrection for dead Israel. The Lord declares, “I will put my breath [there’s that third meaning of ruakh–God’s spirit, God’s very life] in you, and you will live. I will plant you on your fertile land, and you will know that I am the Lord. I’ve spoken, and I will do it. This is what the Lord says” (37:14). Hope for the future, Ezekiel was convinced, would come from God and God alone, through the gift of God’s life-giving Spirit.

![Title: Descent of the Holy Spirit [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/El_Greco_006.jpg)

Another ghost story will also be told in churches around the world this Sunday. Jesus had promised his followers, “Look, I’m sending to you what my Father promised, but you are to stay in the city until you have been furnished with heavenly power” (Lk 24:49). So they had remained in Jerusalem; as our story begins, they have been there, waiting and praying, ever since Jesus’ resurrection. It is now Pentecost, the Jewish festival held 50 days after Passover.

Suddenly, the room where they are praying is filled with wind and flame, and each person gathered in that room is filled with an overpowering urge to speak! They pour out into the street, praising God, and discover to their astonishment and delight that everyone in that crowd, Pentecost pilgrims who had come to Jerusalem from across the Roman world, understands perfectly what they are saying: “we hear them declaring the mighty works of God in our own languages!” (Acts 2:11).

Ezekiel’s ghost story reminds us of our beginning–of how God created we humans from the ground, breathing life into us .

Luke’s ghost story, in Acts 2, also takes us back to Genesis–this time, to the tower of Babel.

Too often, preachers and teachers of Scripture (including me!) have described what happened on Pentecost as undoing the curse of Babel, as though cultural, racial, and linguistic diversity were problems to overcome. But that is not at all what Luke says! This passage does not say that, filled with the Spirit, the people all started speaking the same language—that all cultural and ethnic distinctiveness was denied or undone. The Spirit does not return them to “one language and the same words” (Genesis 11:1). Instead, each group hears God’s praise in its own language.

In Ezekiel’s vision, God’s Spirit undoes the exile, bringing those who had thought themselves as good as dead back home. On Pentecost, God’s Spirit undoes fear, mistrust, and division, enabling the church born on that day to experience unity in diversity.

Perhaps, like Ezekiel’s community, we have experienced abandonment and despair. Certainly, the real curse of Babel– our fear and mistrust of difference–has stricken deeply into our community, even into our families, bringing division and confusion. The solution, for us as for them, is God’s Spirit: the Holy Ghost!

That may be hard for us to hear. Ghosts are scary, after all. Why should we exchange the visible and tangible, the solid and certain, for the invisible, mysterious, unpredictable world of God’s spirit? Quite simply, because we must. We need God’s spirit because we do not have the answers we seek, and we cannot find them. We need the gift of God’s spirit to empower and enliven us, to renew and reunite us.

My teacher W. Sibley Towner (may light perpetual shine upon him!) put it this way: “We need all the energy and effort we can muster to concentrate on the whisperings of the only ghost that matters, whose name is Holy. This spirit who proceeds from God doesn’t rock in chairs or frighten dogs, but plants winsome words in the human heart that yield great fruit if the heart is supple and ready.”

So may it be for you and yours this day. God bless you–and Happy Pentecost!

AFTERWORD:

The image at the head of this blog, “Ezekiel in the Valley of the Dry Bones,” is an anonymous and undated wood carving from St. Nicholas Church, Deptford Green, United Kingdom. I found this image at Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=55163 [retrieved May 13, 2024]. Original source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St._Nicholas%27_Church,_Deptford_Green,_SE8_-_carved_panel_representing_Ezekiel_in_the_Valley_of_the_Dry_Bones_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1501992.jpg.

The photographs above of unburied bones and corpses come from the battlefields of the American Civil War: the first from Cold Harbor, in Virginia, the second from Gettysburg, in Pennsylvania.

This week, as Christian pastors and laity alike turn in their devotions to reflection on Jesus’ betrayal, trial, torture, and death, it seems appropriate to turn to the witness of the apostle Paul, our first-century peer.

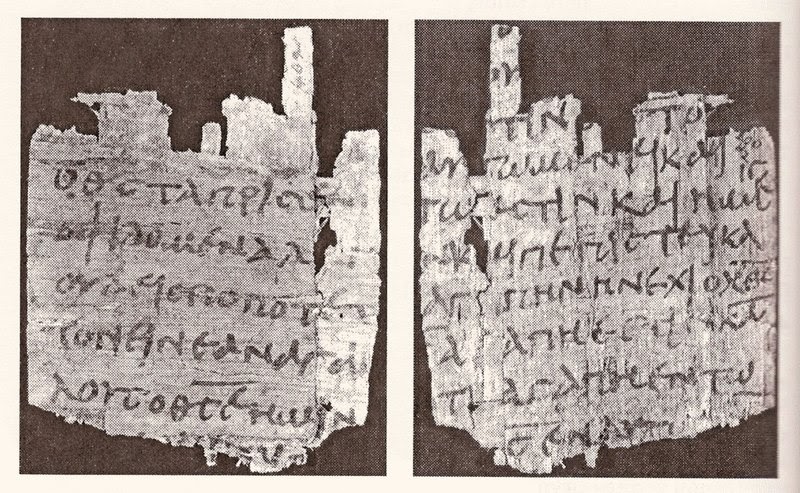

This week, as Christian pastors and laity alike turn in their devotions to reflection on Jesus’ betrayal, trial, torture, and death, it seems appropriate to turn to the witness of the apostle Paul, our first-century peer. So–when and how did Jesus send him? In

So–when and how did Jesus send him? In  Paul freely acknowledges that this is absurd on its face:

Paul freely acknowledges that this is absurd on its face: This means that the death of Jesus on the cross is not just about Jesus (

This means that the death of Jesus on the cross is not just about Jesus ( In our American date format, today is 3/14, which is also, as it happens, pi to the first two digits–making March 14 Pi Day! To refresh from high school geography, pi is the ratio between the circumference of a circle and its diameter–so, if you know the radius of a circle, you can use pi to calculate its circumference (2πr) or its area (πr squared: prompting the very bad pun, “No, pie are round; cornbread are square”). That ratio is, approximately, 3.14159–although mathematicians have now calculated its value out

In our American date format, today is 3/14, which is also, as it happens, pi to the first two digits–making March 14 Pi Day! To refresh from high school geography, pi is the ratio between the circumference of a circle and its diameter–so, if you know the radius of a circle, you can use pi to calculate its circumference (2πr) or its area (πr squared: prompting the very bad pun, “No, pie are round; cornbread are square”). That ratio is, approximately, 3.14159–although mathematicians have now calculated its value out

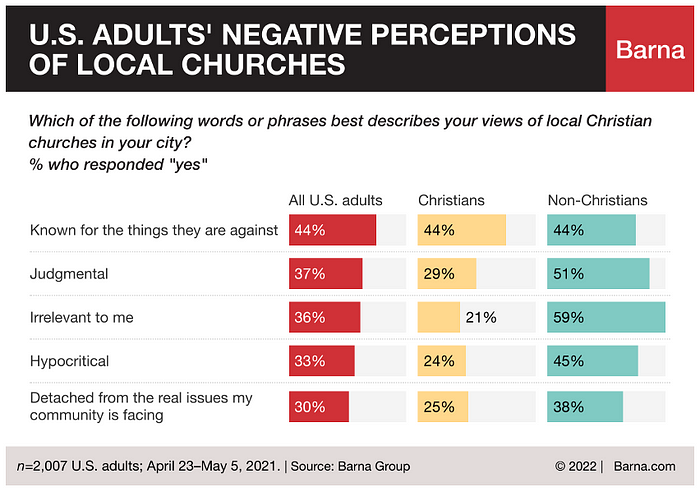

Evangelical pastor and author Brian Zahnd is concerned that much of American Christianity today is characterized, not by service or kindness, but by fear and anger–even hatred. Challenging his fellow pastors and leaders, Zahnd says,

Evangelical pastor and author Brian Zahnd is concerned that much of American Christianity today is characterized, not by service or kindness, but by fear and anger–even hatred. Challenging his fellow pastors and leaders, Zahnd says,

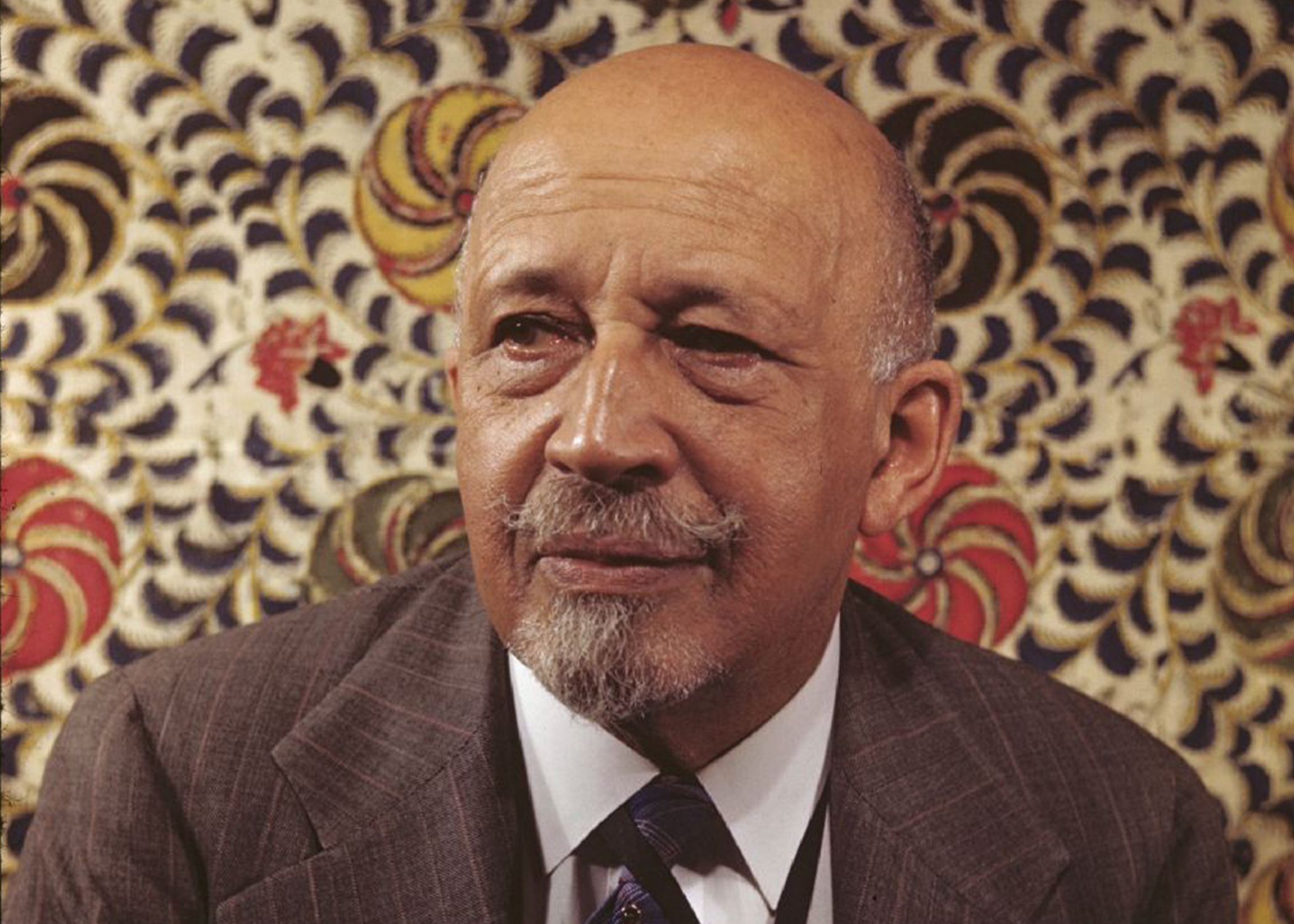

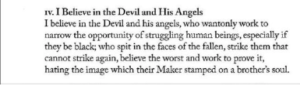

I learned of this piece through a concert at my home church, St. Paul’s UMC, by Archipelago, an extraordinary vocal ensemble conducted by Caron Daley of Duquesne University. The climax of the evening was a wonderful choral setting of DuBois’ “Credo” by African American composer

I learned of this piece through a concert at my home church, St. Paul’s UMC, by Archipelago, an extraordinary vocal ensemble conducted by Caron Daley of Duquesne University. The climax of the evening was a wonderful choral setting of DuBois’ “Credo” by African American composer

This day, in the dead of winter, is associated with hope for the return of warmer weather–but not too soon. A “false spring” after all may be followed by a killing frost, wiping out trees that have budded too early, and threatening lambs born out of season. Therefore, sunny weather on this midwinter day (so that a groundhog can see its shadow!) is held to be a bad omen of more bleak days ahead, while cold and cloudy weather appropriate to the season augurs the swift return of sunshine and greenery.

This day, in the dead of winter, is associated with hope for the return of warmer weather–but not too soon. A “false spring” after all may be followed by a killing frost, wiping out trees that have budded too early, and threatening lambs born out of season. Therefore, sunny weather on this midwinter day (so that a groundhog can see its shadow!) is held to be a bad omen of more bleak days ahead, while cold and cloudy weather appropriate to the season augurs the swift return of sunshine and greenery.![Title: Presentation in the Temple [Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/C_FirstSundayafterChristmas.jpg) This tapestry depicting Luke’s scene is from the Abbey Church of St. Walpurga in Virginia Dale, Colorado. The Order of St. Walpurga was established in the 11th century in Bavaria. The nuns of that order fled to the United States in 1935 to escape the Nazis, and settled in the Colorado mountains. The walls of their church are lined with tapestries like this one of the Presentation of the Lord, all inspired by biblical texts.

This tapestry depicting Luke’s scene is from the Abbey Church of St. Walpurga in Virginia Dale, Colorado. The Order of St. Walpurga was established in the 11th century in Bavaria. The nuns of that order fled to the United States in 1935 to escape the Nazis, and settled in the Colorado mountains. The walls of their church are lined with tapestries like this one of the Presentation of the Lord, all inspired by biblical texts. Although Jesus has come for everyone, not everyone will receive him. Simeon’s words prefigure Jesus’ coming rejection–his trial, condemnation, and crucifixion, and so Mary’s coming sorrow: “And a sword will pierce your innermost being too” (Luke 2:35). In this season after Epiphany, we rightly remember that Jesus’ way leads us to God’s light–but that way must pass through the darkness of the cross. Simeon offers no illusions that God’s salvation comes easily, without opposition or conflict.

Although Jesus has come for everyone, not everyone will receive him. Simeon’s words prefigure Jesus’ coming rejection–his trial, condemnation, and crucifixion, and so Mary’s coming sorrow: “And a sword will pierce your innermost being too” (Luke 2:35). In this season after Epiphany, we rightly remember that Jesus’ way leads us to God’s light–but that way must pass through the darkness of the cross. Simeon offers no illusions that God’s salvation comes easily, without opposition or conflict.