In Genesis 2:1-3, the Sabbath is the climax of creation. The first six days of God’s creation unfold in Genesis 1 in a carefully ordered, three by three pattern. Day One (1:3-5), the creation of light (Hebrew ‘or) parallels Day Four (1:14-19), the creation of the sun, moon, and stars, called lights (Hebrew me’orot) in the sky. Day Two, the creation of the sky dome, leaving the waters of the sea under the heavens (1:6-8), parallels Day Five, when God creates birds to fly in the air and fish to swim in the sea (1:20-23). God’s two creative acts on Day Three, the creation of dry land (1:9-10) and the creation of plants (1:11-13) parallel God’s two acts 0n Day Six: the creation of land animals, both wild and domestic (1:24-25), and the creation of human beings (1:26-31). Day Seven thus stands apart, as a day without parallel.

We could conclude from this structure that the Sabbath comes after creation is finished (see Exod 20:11). The Samaritan Pentateuch (a version of the first five books of the Bible used by the Samaritans), the Greek Septuagint, and the Syriac all say that God completed God’s work on the sixth day, a reading that the CEB follows (see Genesis 2:2). But I believe that it is better to stay with the Hebrew text here, as the NRSV does, and to see the Sabbath as the day when creation is completed. For the priests who wrote Genesis 2:1-3, Sabbath was part of the very structure of reality, woven into the warp and woof of the cosmos.

When God creates the world in Genesis 1, God calls into being something new: something that is not God. Some religions have seen the world itself as divine.

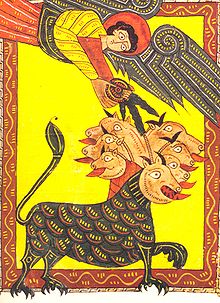

Indeed, the Semitic words for Sun,

Moon,

and even the stars

were also the names of gods and goddesses–which is likely why those terms are not used in Genesis 1:14-19. The priests of ancient Israel insisted that the world is authentically distinct and separate from God. The sun and moon are not gods, and the stars are not goddesses. They are merely lights in the sky. This is a long way from astronomy, but the “disenchantment” of the natural world that it represents would make science possible.

As theologian and particle physicist John Polkinghorne observes, in Genesis 1 God endows the universe “with the power of true becoming” (The Faith of a Physicist [Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994], 81): that is, God enables the world to participate in its own creation! So, the earth brings forth plant (1:11) and animal life (1:24), and the waters bring forth “swarms of living creatures” (1:20). This too is a long way from biology, but it is a view of the world consistent with the ideas of evolution and genetics. Further, provision is made for the continual recreation and renewal of God’s world (1:11-12, 22, 28), so that it can sustain itself.

Calling an autonomous universe into being “involves divine acceptance of the risk of the existence of the other” (Polkinghorne, 81). But the God of Genesis is not anxious or controlling. God loves the world God makes! Again and again through the first six days, God celebrates the beauty and wholeness of God’s world, calling the creation “good” (1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25, 31). Then, on the seventh day, God stops working, and rests: a profound expression of confidence in the world that God has made. God trusts God’s creation enough to declare it finished, and to rest.

The renowned Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann affirms,

The day of cessation from work declares that God’s creation is, at root, an unanxious environment for life that is not defined by energetic productivity or self-preoccupied consumption, but is defined by the peaceableness that has confidence in the reliability of the world as God’s creation without excessive exertion on the part of God or of humankind (An Introduction to the Old Testament: The Canon and Christian Imagination [Louisville: Westminster-John Knox, 2003], 35-36).

Creation is not abandoned by God, and left to its own devices. The God of Genesis is certainly not the clockmaker god of the Deists, who sets the universe running and then departs.

But neither is the God we meet in Genesis some cosmic puppet master, the lone real actor in the cosmic drama. Genesis 2:1-3 affirms rather that God rests, and in love and confidence lets the world go.

John Wesley, who urged his preachers never to be “triflingly employed,” has a great deal to answer for! “Letting go” is especially hard for clergy. Resting seems lazy and unproductive–and certainly, in the church there is always more to do! But our feverish need to be busy may show, not zeal for our Father’s business, but anxiety! Our drive to be involved in everything may actually reflect our desire to be in control.

Our obsession with effectiveness and efficiency, however, is neither effective nor efficient! Our most productive periods often come when we are not working, when in stillness and calm we open ourselves to new insights, through the moving of the Spirit–when we follow God’s example, and embrace Sabbath rest.

Genesis 2:3 declares that “God blessed the seventh day, and hallowed it.” In Exodus 20:8-11, God’s rest, together with God’s blessing on and sanctification of that rest, is the reason that we are to remember and sanctify the Sabbath day.

Still today, pious Jews chant Genesis 2:1-3 before praying the kiddush, the prayer over wine to sanctify the Sabbath. Sabbath observance has long been a distinguishing mark of people Israel–which is why Jesus’ apparent disregard of the Sabbath brought such a strong response from the religious leaders of his day. But Jesus’ insistence on healing on the Sabbath shows, not disrespect for the Sabbath, but a desire to reclaim the Sabbath. Jesus said,

The Sabbath was created for humans; humans weren’t created for the Sabbath. This is why the Human One is Lord even over the Sabbath (Mark 2:27-28).

What better time to set people free than the seventh day, when God completed God’s creation, and celebrated by setting the world free?

AFTERWORD:

The Bible Guy welcomes the incoming class of students to Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, and also welcomes a great crop of new faculty! Pray for us, please, as together we pursue Christ’s call!