FOREWORD: I am reposting this (lightly edited) blog from two years ago. My apologies for not posting yet in this new year–I contracted COVID at our Christmas Eve service, and am really only now getting my bearings! Thankfully, in the Tuell household we are all vaccinated and boosted, and so none of us was ever in real danger–but make no mistake, friends. The new COVID variant is even more virulent, and bodes to be just as deadly, as the last: here in Allegheny County, it is killing about a person a day. If you are not yet vaccinated, or have not yet gotten the booster, please go to your doctor or drug store IMMEDIATELY: not just for yourself, but for your family and your community.

In the United States (and Canada, too), Friday February 2 is Groundhog Day. We will wait with trepidation to see if a groundhog (in Pennsylvania, THE Groundhog, Punxsatawney Phil) sees his shadow–because if he does, then there will be six more weeks of winter. Where in the world could this bizarre custom have come from?

February 2 marks the quarter-year: midwinter, as Hallowe’en is midautumn. Celts called this day Imbolc, and identified it as the time when ewes begin to give milk, in preparation for spring lambing. According to Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, shepherds in Roman times also celebrated a midwinter festival on February 2.

This day, in the dead of winter, is associated with hope for the return of warmer weather–but not too soon. A “false spring” after all may be followed by a killing frost, wiping out trees that have budded too early, and threatening lambs born out of season. Therefore, sunny weather on this midwinter day (so that a groundhog can see its shadow!) is held to be a bad omen of more bleak days ahead, while cold and cloudy weather appropriate to the season augurs the swift return of sunshine and greenery.

This day, in the dead of winter, is associated with hope for the return of warmer weather–but not too soon. A “false spring” after all may be followed by a killing frost, wiping out trees that have budded too early, and threatening lambs born out of season. Therefore, sunny weather on this midwinter day (so that a groundhog can see its shadow!) is held to be a bad omen of more bleak days ahead, while cold and cloudy weather appropriate to the season augurs the swift return of sunshine and greenery.

In addition to its ancient folk connections, this day also has a biblical warrant: by the Western Church’s reckoning, February 2 comes forty days after Christmas, the celebration of Jesus’ birth. Leviticus 12:2-8 stipulates the rites of purification for cleansing from the ritual uncleanness caused by childbirth: for a baby boy, 7 days of impurity, followed by an additional 33 days during which the mother “must not touch anything holy or enter the sacred area” (Lev 12:4).

Luke 2:22-40 records that Joseph and Mary, as observant first-century Jews, made the pilgrimage to the Jerusalem temple with their son Jesus “[w]hen the time came for their ritual cleansing, in accordance with the Law from Moses” (Luke 2:22): that is, forty days after Jesus’ birth. In Roman Catholicism prior to Vatican II, this day was accordingly called “the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin;” today it is known as “the Presentation of the Lord.”

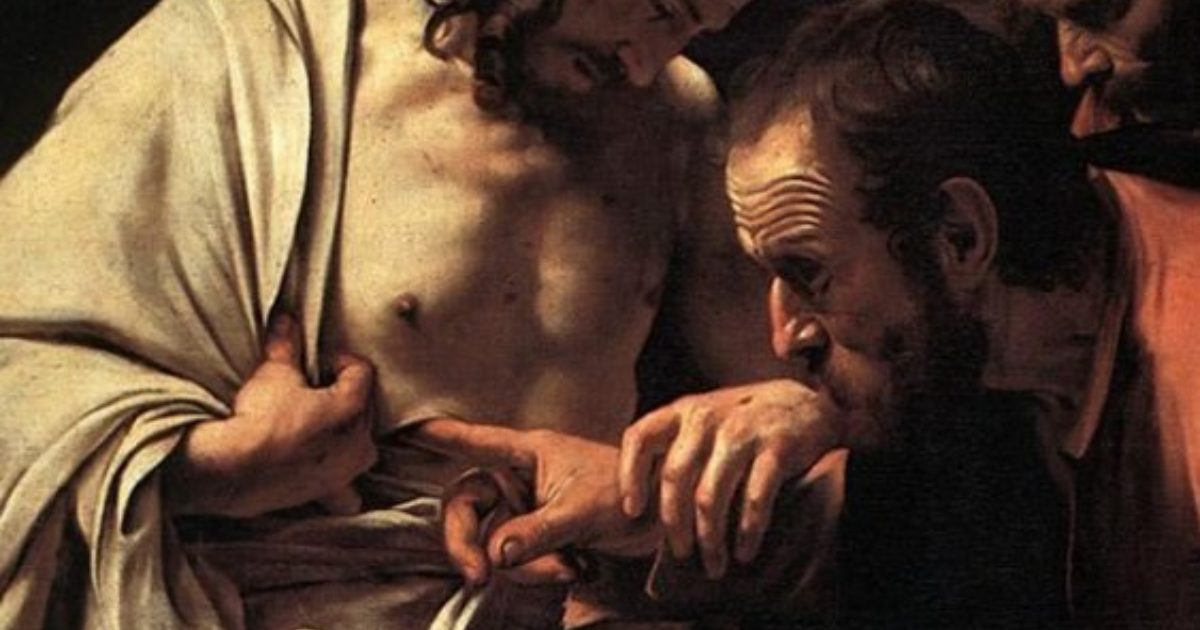

![Title: Presentation in the Temple [Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/C_FirstSundayafterChristmas.jpg) This tapestry depicting Luke’s scene is from the Abbey Church of St. Walpurga in Virginia Dale, Colorado. The Order of St. Walpurga was established in the 11th century in Bavaria. The nuns of that order fled to the United States in 1935 to escape the Nazis, and settled in the Colorado mountains. The walls of their church are lined with tapestries like this one of the Presentation of the Lord, all inspired by biblical texts.

This tapestry depicting Luke’s scene is from the Abbey Church of St. Walpurga in Virginia Dale, Colorado. The Order of St. Walpurga was established in the 11th century in Bavaria. The nuns of that order fled to the United States in 1935 to escape the Nazis, and settled in the Colorado mountains. The walls of their church are lined with tapestries like this one of the Presentation of the Lord, all inspired by biblical texts.

Mary is in the center, followed by Joseph (in the slouch hat). Joseph carries the two turtledoves that Leviticus 12:8 says a poor family may offer instead of a sheep as a sacrifice (see Luke 2:24).

Also pictured is Simeon, who had been promised “that he wouldn’t die before he had seen the Lord’s Christ” (Luke 2:26). Simeon holds baby Jesus, praises God for him, and prays a beautiful prayer, called (after its opening words in Latin) the Nunc dimittis:

Now, master, let your servant go in peace according to your word,

because my eyes have seen your salvation.

You prepared this salvation in the presence of all peoples.

It’s a light for revelation to the Gentiles

and a glory for your people Israel (Luke 2:29-32).

The Latin inscription on the St. Walpurga abbey tapestry refers to this prayer: Lux ad revelationem Gentium means “a light for revelation to the Gentiles.” Simeon’s prayer in turn alludes to several passages in Isaiah (see Isa 42:6; 49:6; 51:4; 60:3), but particularly to Isaiah 49:5-6, from the second Servant Song:

And now the Lord has decided—

the one who formed me from the womb as his servant—

to restore Jacob to God,

so that Israel might return to him.

Moreover, I’m honored in the Lord’s eyes;

my God has become my strength.

He said: It is not enough, since you are my servant,

to raise up the tribes of Jacob

and to bring back the survivors of Israel.

Hence, I will also appoint you as light to the nations

so that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth.

The salvation offered through Jesus is for everyone.

After this prayer of thanksgiving, Simeon gives to Mary a much more somber word:

This boy is assigned to be the cause of the falling and rising of many in Israel and to be a sign that generates opposition so that the inner thoughts of many will be revealed (Luke 2:34-35).

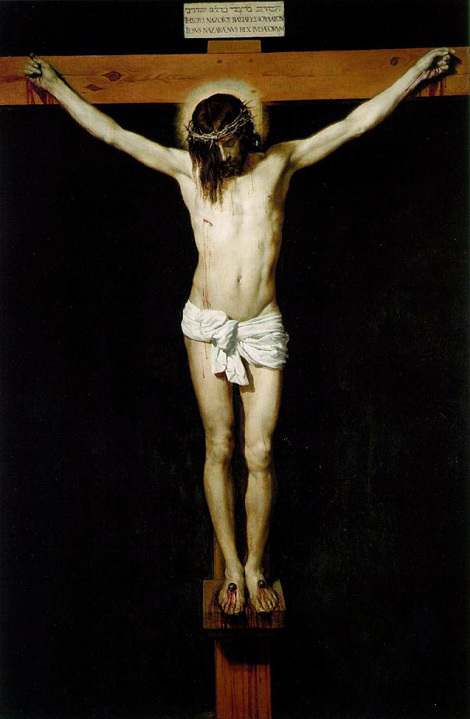

Although Jesus has come for everyone, not everyone will receive him. Simeon’s words prefigure Jesus’ coming rejection–his trial, condemnation, and crucifixion, and so Mary’s coming sorrow: “And a sword will pierce your innermost being too” (Luke 2:35). In this season after Epiphany, we rightly remember that Jesus’ way leads us to God’s light–but that way must pass through the darkness of the cross. Simeon offers no illusions that God’s salvation comes easily, without opposition or conflict.

Although Jesus has come for everyone, not everyone will receive him. Simeon’s words prefigure Jesus’ coming rejection–his trial, condemnation, and crucifixion, and so Mary’s coming sorrow: “And a sword will pierce your innermost being too” (Luke 2:35). In this season after Epiphany, we rightly remember that Jesus’ way leads us to God’s light–but that way must pass through the darkness of the cross. Simeon offers no illusions that God’s salvation comes easily, without opposition or conflict.

The fifth person pictured on the St. Walpurga tapestry is Anna, an 84 year old widow who “never left the temple area but worshipped God with fasting and prayer night and day (Luke 2:37). Luke does not quote her words, as he does Simeon’s. But he does tell us that her words are directed, not just privately to the family, but publicly, to everyone in earshot: “She approached at that very moment and began to praise God and to speak about Jesus to everyone who was looking forward to the redemption of Jerusalem” (Luke 2:38). In Luke’s gospel, from the very first, anyone with eyes to see and a heart to believe knows who Jesus is!

February 2 has one more traditional church connection–and one more name! In the Western Christian calendar, this midwinter day is often called Candlemas, and was traditionally when the candles used in the coming year were blessed. Friends, may we remember on this day of light and hope that Jesus leads us in the way of “[God’s] salvation . . . a light for revelation to the Gentiles and a glory for your people Israel.”

AFTERWORD:

A prayer for this day, from Revised Common Lectionary Prayers copyright © 2002 Consultation on Common Texts admin. Augsburg Fortress.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-1127577455-af4de78e939a40d9b37032ef9e24fd8a.jpg)

When I visit my father, who turns 88 this month (Happy birthday, Daddy!). we often watch old movies together–especially old Westerns. You never have to wonder who the good guys are in those old oaters! They are always dressed the part: clean-cut, clean shaven, and wearing white hats. The villains by contrast are scruffy, mustachioed, and wear black.

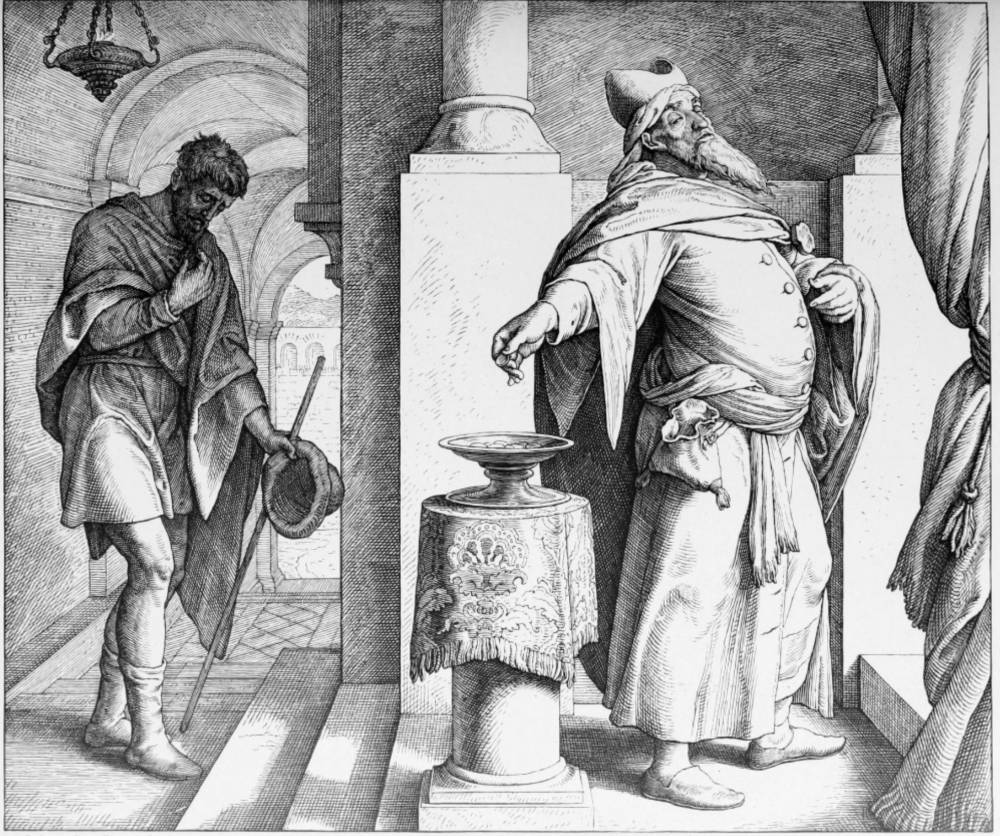

When I visit my father, who turns 88 this month (Happy birthday, Daddy!). we often watch old movies together–especially old Westerns. You never have to wonder who the good guys are in those old oaters! They are always dressed the part: clean-cut, clean shaven, and wearing white hats. The villains by contrast are scruffy, mustachioed, and wear black. So, when “Have Gun, Will Travel” appeared on television in 1957, it was something of a shock. Its main character, Paladin (expertly portrayed through its six-year run by Richard Boone), wasn’t a sheriff or a cowboy, but a gunfighter for hire. Paladin wore black. He looked, dressed, and often talked like a villain—yet he was the hero. Sometimes, in those short, often very well-written episodes, Paladin would wind up changing sides–fighting for the people he believed to be in the right, rather than the ones who had hired him.

So, when “Have Gun, Will Travel” appeared on television in 1957, it was something of a shock. Its main character, Paladin (expertly portrayed through its six-year run by Richard Boone), wasn’t a sheriff or a cowboy, but a gunfighter for hire. Paladin wore black. He looked, dressed, and often talked like a villain—yet he was the hero. Sometimes, in those short, often very well-written episodes, Paladin would wind up changing sides–fighting for the people he believed to be in the right, rather than the ones who had hired him. Likewise, in the first century, the tax collector most definitely would have been seen as the villain. Tax collectors were collaborators with the Roman military occupation. They were famously corrupt, typically collecting from the people far more than the Romans actually demanded, and living well off the proceeds (

Likewise, in the first century, the tax collector most definitely would have been seen as the villain. Tax collectors were collaborators with the Roman military occupation. They were famously corrupt, typically collecting from the people far more than the Romans actually demanded, and living well off the proceeds (

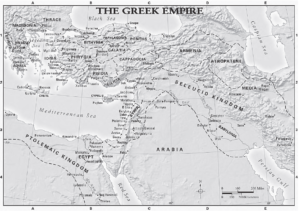

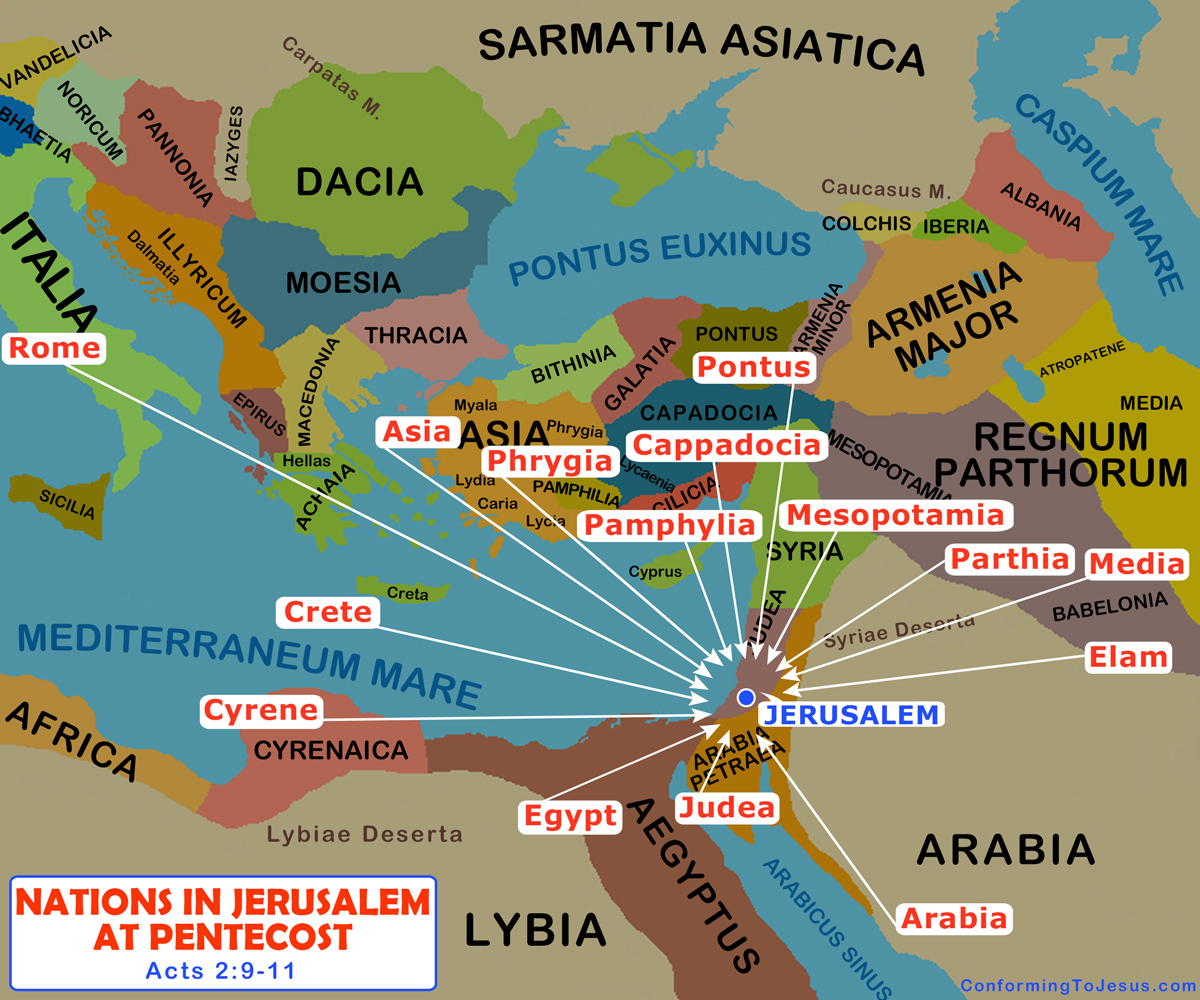

Sunday is Pentecost, which means that bewildered lay readers (and more than a few preachers!) across the church will once again be wrestling with the jawbreaking, tongue-tangling list of place names (go

Sunday is Pentecost, which means that bewildered lay readers (and more than a few preachers!) across the church will once again be wrestling with the jawbreaking, tongue-tangling list of place names (go  Meanwhile, Jesus’ followers were waiting in Jerusalem as he had commanded them (

Meanwhile, Jesus’ followers were waiting in Jerusalem as he had commanded them (

![Title: Prophet Miriam [Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/miriam33172410852_bcf5c473db_k.jpg)

In the early church, when believers met in this holy season, they would greet one another with a hearty and enthusiastic Christe anesti–“Christ is risen!”–to which the only possible response is Allthos anesti–“He is risen indeed!”

In the early church, when believers met in this holy season, they would greet one another with a hearty and enthusiastic Christe anesti–“Christ is risen!”–to which the only possible response is Allthos anesti–“He is risen indeed!”

As we approached Jerusalem

As we approached Jerusalem