![Title: St. Savin - Calling of Abraham [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/00002314.jpg)

The Hebrew Bible reading for Sunday is Abram’s call (Genesis 12:1-4a). It is tempting for us, with the benefit of biblical hindsight, to think that this passage marks the beginning of Abram’s singular, goal-oriented pursuit of God’s promises: that he would find a homeland, become prosperous, and have many children. But our text cannot support such a reading. What Abram is leaving behind is defined, clearly and repeatedly: “Go from your country and from your family and from your home” (Gen 12:1, my translation)—leave, in short, all that is familiar. But as for where he is going, God says only that it is “the land that I will show you.” Abram sets out for—wherever. He and Sarai are given no map, no specific heading. Instead, they are required to be open to God’s direction and guidance all along the way.

We should not expect our own path to be any different than theirs: whether as individuals, as congregations, or as the church. We as well cannot know what the future might bring—and so, to limit our planning and dreaming to a simple extrapolation of what we now know may be to dream wrongly, to plan awry. Like Abram, we are called to lives of open expectation and radical trust in the God who goes before us.

The anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing, a classic of Christian spirituality, puts it this way:

Your whole life must be one of longing, if you are to achieve perfection. And this longing must be in the depths of your will, put there by God, with your consent. But, a word of warning: he is a jealous lover, and will brook no rival; he will not work in your will if he has not sole charge; he does not ask for help, he asks for you.

While Abram and Sarai are given no specific goal, they are given the assurance of God’s good intentions for them. God declares, “I will make of you a great nation and will bless you. I will make your name respected, and you will be a blessing” (Gen 12:2). However, God’s blessing is not given to Abram for his own sake: to enrich Abram, meet his needs, and make his dreams come true.

This is particularly clear in the Hebrew of Genesis 12:3. While the NRSV of this verse reads, “in you all the families of the earth will be blessed”—implying that the blessing on Abram is primary, and that the blessing on the “families of the earth” follows from it—the Hebrew reads, wenibreku beka: that is, “they will bless themselves by you” (see the text notes in the NRSV, NRSVue, and CEB). The point, it seems, is that others, challenged and motivated by what they see in Abram and his heirs, will say to one another, “May life be for you as it has been for Abram.” Abram is blessed for the sake of others.

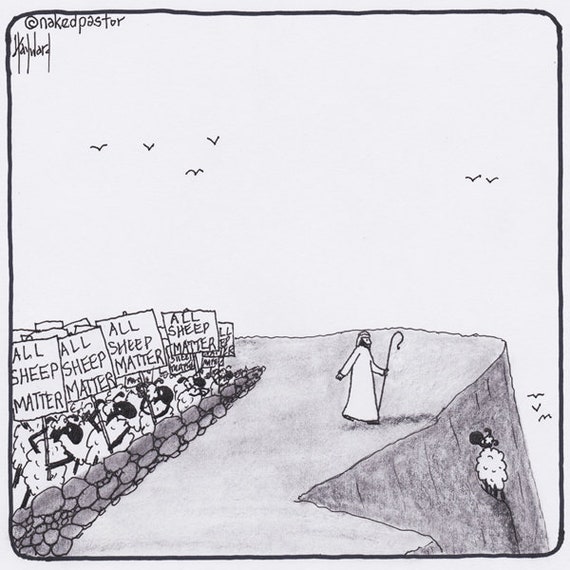

For us as well, the purpose of God’s blessing is “so that you will be a blessing” (Gen 12:2, NRSVue). If our planning, as a church or as a denomination, is solely about our survival, our goals will be far too small. If we seek a future that will bless and enrich us, then even if that dream is realized, we will find it to have been the wrong dream! Better questions, which will guide us into God’s dream for us, are: How can we be a blessing to others? How can we be used by God in the continual reformation of Christ’s church? How can we be agents of God’s kingdom in the world?

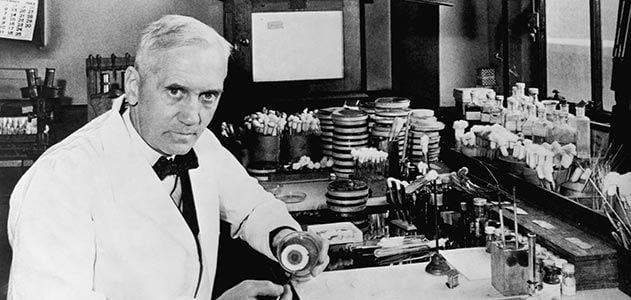

The story of Sir Alexander Fleming, discoverer of penicillin, dramatically demonstrates the limitations of a focused, goal-directed approach to life. Fleming discovered this marvelous antibiotic in 1928, when bacterial cultures growing in petri dishes in his lab were contaminated by mold spores. As the mold spread, the bacteria died. Penicillin was discovered, not as the end of a deliberately focused research program, but by accident!

But then again, “accident” may not be the right word. Much like Abram and Sarai, Alexander Fleming was heading toward a goal he himself did not choose and could not have foreseen. He discovered penicillin, we might say, because he was open to discovery, and so found himself in the right place at the right time. We Christians call this “providence.”

A story is told about Sir Fleming that may not be true, but deserves to be. Late in his life, he was given a tour of an antiseptic, gleaming, state-of-the-art medical lab. Someone said to him, “Imagine what you could have discovered if you had had all of this at your disposal!” Fleming sardonically replied, “Not penicillin.”

This Lent, as we reflect on our calling and look into our futures, God grant that we might not be found focused on our goals and the pursuit of our dreams. May we instead discern God’s dream for us, by asking how we might become a blessing: to our church, to our city, and to our hurting world. May we be, not cold, antiseptic, and closed-minded, but like Abram and Sarai open to God’s unexpected gifts of grace and direction all along our way.

AFTERWORD:

The fresco at the head of this blog depicting Abram’s call is from the upper south register of the nave of Abbaye de Saint-Savin in Vienne, France. It is taken from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=33460 [retrieved February 27, 2023]. Original source: image donated by Jim Womack and Anne Richardson.

The digital artwork for “The Cloud of Unknowing” is by Roman Verostko.

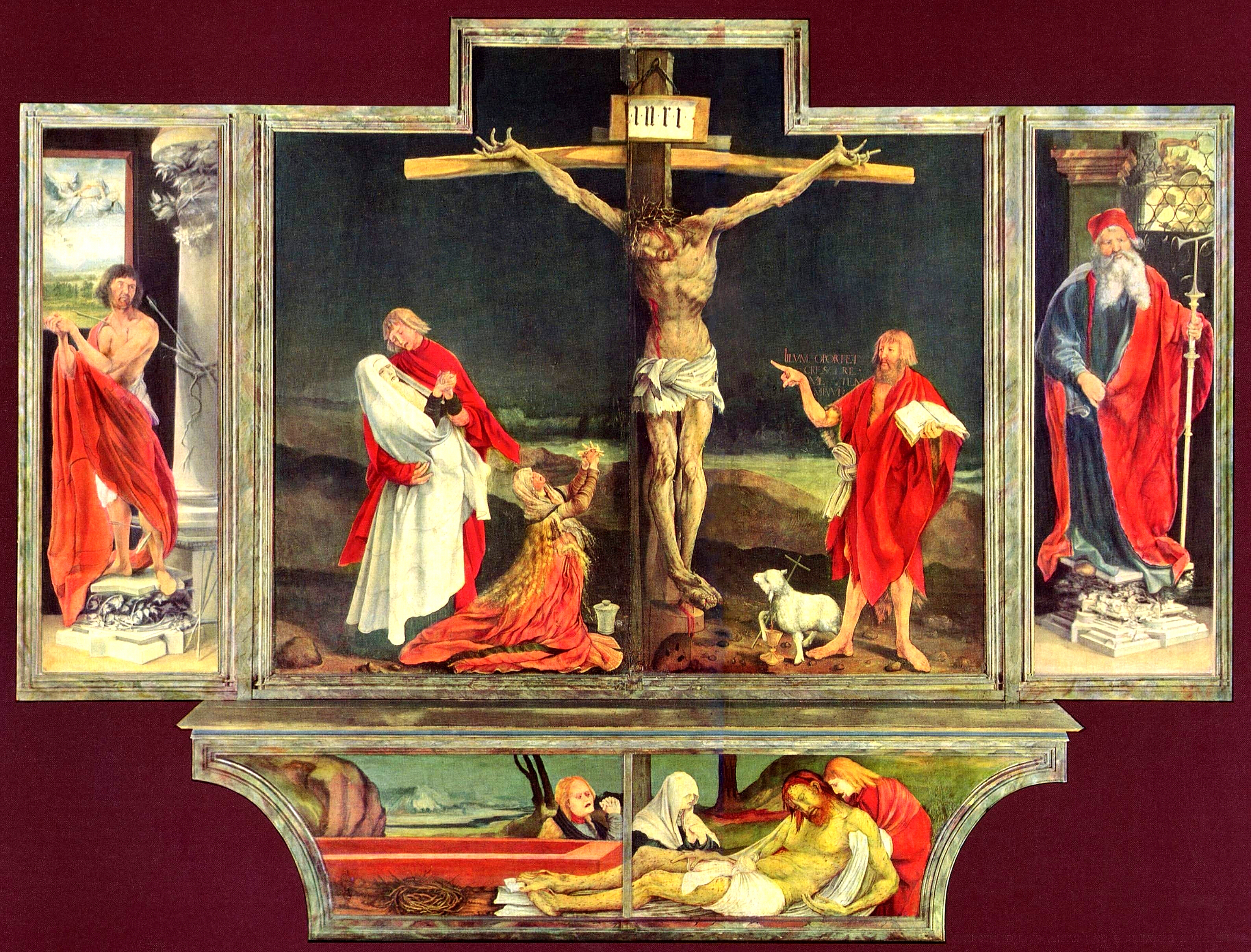

But what would this word have meant to the writers, and hearers, of the Gospels? The verb metamorphoo is not used in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of Jewish Scripture), and in our New Testament, it appears only four times. Two of these are the accounts of Jesus’ transfiguration in Matthew and Mark (

But what would this word have meant to the writers, and hearers, of the Gospels? The verb metamorphoo is not used in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of Jewish Scripture), and in our New Testament, it appears only four times. Two of these are the accounts of Jesus’ transfiguration in Matthew and Mark (

![Title: Star of Bethlehem with Pomegranate Trees [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/ACT0012.jpg)

If you are wondering what any of this has to do with the season of Advent, or with the birth of our Lord, may I remind you that the alternate Psalm for this coming Sunday is Luke’s Song of Mary (

If you are wondering what any of this has to do with the season of Advent, or with the birth of our Lord, may I remind you that the alternate Psalm for this coming Sunday is Luke’s Song of Mary (

If you are a fan of the television quiz show “Jeopardy,” a fellow Bible wonk, or just a person of faith on social media, chances are that you are aware of the recent flap over a “Final Jeopardy” answer in the recent

If you are a fan of the television quiz show “Jeopardy,” a fellow Bible wonk, or just a person of faith on social media, chances are that you are aware of the recent flap over a “Final Jeopardy” answer in the recent