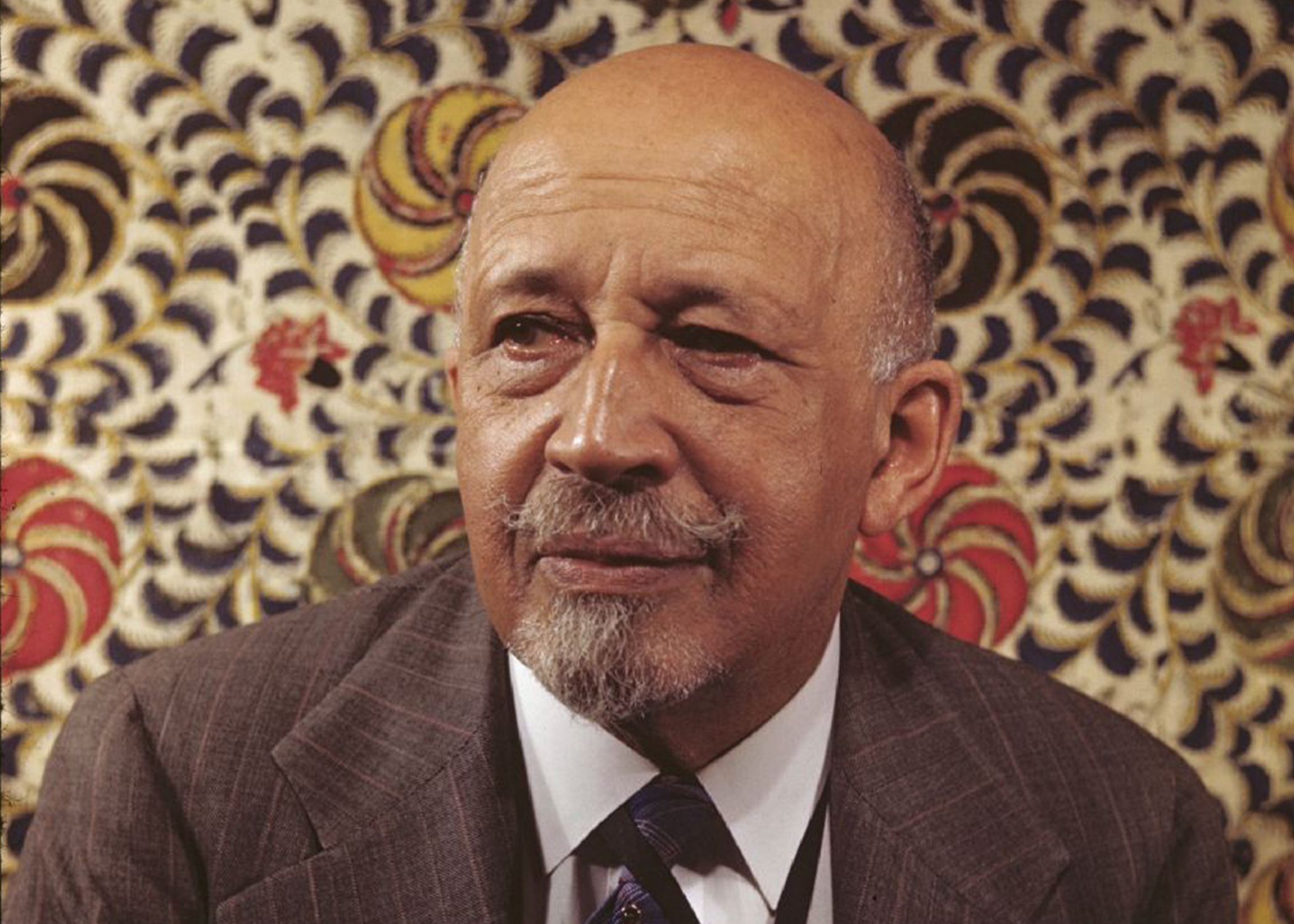

In this Black History Month, I am remembering and celebrating W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963), a pivotal figure in American history. Du Bois was an educator (serving as a professor at Fisk University and Atlanta University), author (The Souls of Black Folk, Dusk of Dawn, and his posthumously published Autobiography), and a tireless activist and advocate for racial equality (he was the founder of the Niagara Movement, a parent of the NAACP).

I only recently learned of another important work of Du Bois: his prose poem “Credo,” published in the New York Independent 57 (Oct. 6, 1904): 787.

I learned of this piece through a concert at my home church, St. Paul’s UMC, by Archipelago, an extraordinary vocal ensemble conducted by Caron Daley of Duquesne University. The climax of the evening was a wonderful choral setting of DuBois’ “Credo” by African American composer Margaret Bonds (1913-1972). Although she composed this piece in 1965, it was lost, and only recently rediscovered and published.

I learned of this piece through a concert at my home church, St. Paul’s UMC, by Archipelago, an extraordinary vocal ensemble conducted by Caron Daley of Duquesne University. The climax of the evening was a wonderful choral setting of DuBois’ “Credo” by African American composer Margaret Bonds (1913-1972). Although she composed this piece in 1965, it was lost, and only recently rediscovered and published.

Several features of Du Bois’ “Credo” stand out to this Bible Guy and United Methodist minister. First is Du Bois’ understanding, already in 1904, that God “made of one blood all the races that dwell on the earth.”

I had attributed this insight, that in light of Genesis all the people of the earth are one human family, to African American theologian George Kelsey (1910-1996), who was the Henry Anson Buttz Professor emeritus of Christian Ethics at Drew University, where he taught for 24 years, and who was a mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr. at Morehouse College.

In his book Racism and the Christian Understanding of Man (New York: Scribner, 1965), Kelsey wrote:

All men are equal because God has bestowed upon all the very same dignity. He has created them in His own image and herein lies their dignity. Human dignity is not an achievement, nor is it an intrinsic quality; it is a gift, a bestowal. Christian faith asserts that all men are equally human; all are creatures and all are potentially spiritual sons of God (Kelsey 1965, 87).

But already in 1904, Du Bois wrote that “all men are brothers, varying through Time and Opportunity, in form and gift and feature, but differing in no essential feature, and alike in soul.” Further, Du Bois recognized that affirming our common humanity in no way meant settling for some bland homogeneity. Du Bois fearlessly and joyously affirms “the Negro Race” and “pride of race and lineage and self. . . so deep as to scorn injustice to other selves.”

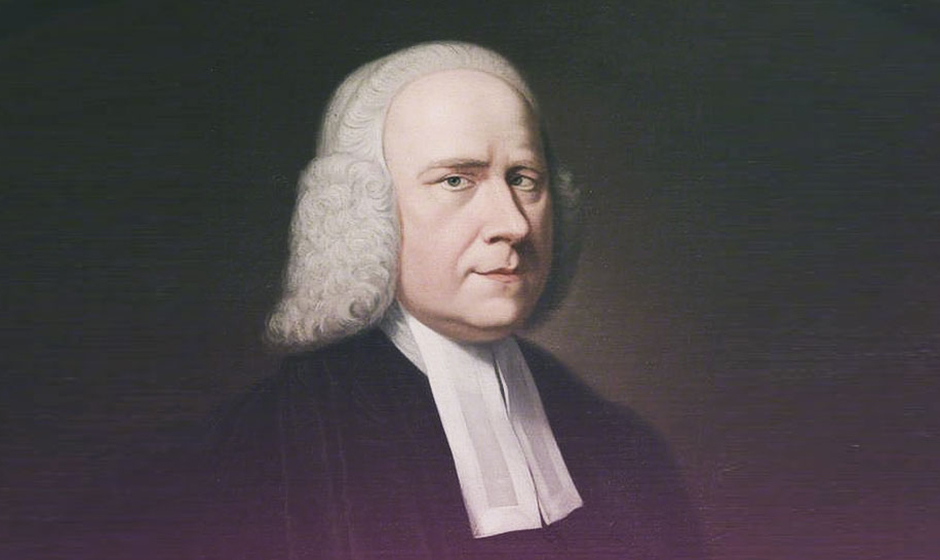

Methodism’s founder John Wesley would applaud Du Bois’ statement that all humanity shares “in the possibility of infinite development,” although of course he would insist that it is through the grace of God and the working of the Spirit that this is so. Further Wesley, who urged his preachers never to be “triflingly employed,” would agree fully with Du Bois’ statement that “Work is Heaven, Idleness is Hell”!

When I heard this piece performed, one part of Du Bois’ “Credo” deeply troubled me–and troubles me still:

I was reminded of a time in chapel at PTS, when an African American student addressed a goodly part of her prayer to Satan, binding him and rejecting his power and presence. At the time, I objected to this: surely, our prayers should be addressed to God alone! But reading Du Bois’ “Credo,” I wonder how much of my refusal to acknowledge the Enemy’s power and influence is a reflection of my own privilege? How often have I been confronted with and threatened by the power of evil in the way that Du Bois describes, and that my Black sisters and brothers face each and every day?

In his City of God (XI, 9), Augustine wrote, “For evil has no positive nature; but the loss of good has received the name ‘evil.’” But I am persuaded that Augustine’s notion that evil is merely the absence of good is far too weak: evil is real, a power and presence in our world. So I acknowledge the importance and symbolic power of the idea of Satan. But I am also persuaded that there is good reason that the historic creeds of the church, unlike Du Bois’ “Credo,” do not confess a “belief” in “the Devil and His Angels.” We are not dualistic bi-theists, friends. Jesus tells his followers,

“I saw Satan fall from heaven like lightning. Look, I have given you authority to crush snakes and scorpions underfoot. I have given you authority over all the power of the enemy. Nothing will harm you. Nevertheless, don’t rejoice because the spirits submit to you. Rejoice instead that your names are written in heaven” (Luke 10:18-20).

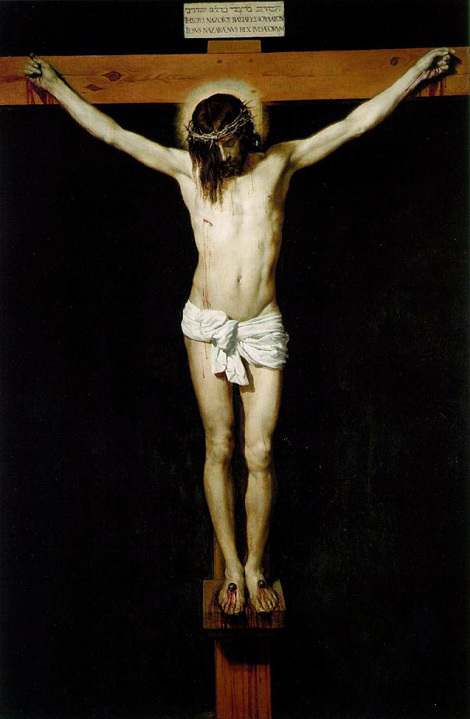

I am persuaded that one huge problem with American Christianity is the degree to which we have behaved as though the Enemy was as powerful in this world as the Lord, to the end that we have embraced a macho warrior “Christ” that bears little resemblance to the Jesus of the Gospels, and a militant “Christianity” likewise divorced from the biblical or historical Church. Further, we are far too ready to project that dualism onto our political issues and adversaries, so that those with whom we disagree become, often quite literally, demonic. In his book The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism (San Francisco: Harper, 2023), Tim Alberta describes the preaching of Greg Locke, leader of the Global Mission Bible Church in Mt. Joliet, Tennessee: “He called Democrats ‘God-denying demons’ and said, ‘You cannot be a Christian and vote Democrat in this nation'” (p. 227).

It is worth taking a little time to recognize the way that the Hebrew word satan and the proper name Satan are used in Scripture. In the New Testament, “Satan” is used thirty-five times as the personal name of a personal devil and spiritual adversary. In the Hebrew Bible, however, the Hebrew term satan often appears with reference to a human enemy (satan is translated “adversary” in the NRSV of 1 Sam 29:4; 2 Sam 19:22; 1 Kgs 5:4; 11:14, 23, 25; and as “accuser” in Ps 109:6).

Satan is definitely used to designate a heavenly being in three places. The first involves the angel of the LORD, who becomes for a time a satan (the NRSV reads “adversary”) to the prophet Balaam (Num 22:22, 32). In the other two cases, Job 1–2 and Zechariah 3:1-2, satan appears with the article, as a title: hassatan, or “the satan.” In both places, the NRSV (following the KJV) used the proper name “Satan;” however, the NRSVue has a much better rendering of the Hebrew: “the adversary.” In each case, the satan is a member of the LORD’s heavenly court, and functions as a kind of celestial prosecuting attorney. So, in the book of Job, the satan accuses the righteous Job of serving the LORD out of self-interest, because God has always blessed him. “But stretch out your hand now, and touch all that he has,” the satan claims, “and he will curse you to your face” (Job 1:11). Similarly, until rebuked by the Lord, the satan stands ready in Zechariah 3 to accuse the high priest Joshua.

This brings us to 1 Chronicles 21:1. Here, instead of hassatan (“the satan”) the Hebrew text reads simply “satan.” Most interpreters take this to mean that Satan here is a proper name–the first such occurrence in Scripture, and the only one in the Hebrew Bible. However, it is also possible to translate the term as “an adversary” (so, for example, Sara Japhet, Chronicles, pp. 374-375; and Paul Redditt, 1&2 Chronicles, p. 147). In that case, some nameless, human advisor would be responsible for influencing David’s decision. Favoring this mundane reading is the absence of any other trace of a personal Satan in Chronicles.

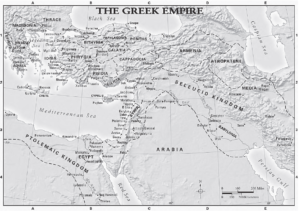

On the other hand, the Greek Septuagint of 1 Chronicles 21:1 reads diabolos here, a Greek word generally translated as “devil” in the New Testament. This is not definitive, as the Septuagint uses diabolos three times with reference to a human enemy (the nameless accuser in Ps 109:6; Haman in Esther 7:1; 8:1; and Antiochus in 1 Macc 1:36). But elsewhere, diabolos is used in all the Hebrew references to a heavenly, supernatural satan, suggesting that the figure in 1 Chronicles was also understood by the Greek translators to be a supernatural adversary. Other elements of the supernatural in 1 Chronicles 21 (David’s conversation with God through the prophet Gad in 1 Chr 21:8-13; the angel with a drawn sword and the fire from heaven in 1 Chr 21:18-27) further support the likelihood that Satan, too, is a supernatural being here.

A modern reader may find it odd that conducting a census should be regarded as an evil act. But David’s census of “men available for military service” (1 Chr 21:5) shows an unwillingness to trust God to defend and deliver Israel. In Chronicles, David is enticed by Satan, yields to that temptation, and carries out an act he knows to be wrong–an act, furthermore, that his general Joab warned him against (1 Chr 21:3).

Satan’s temptation strikes at David’s desires and weaknesses: particularly, it seems, at his pride. Joab’s response to David’s command is a rebuke to such overweening pride: “May the Lord increase his people a hundred times! Sir, aren’t you the king, and aren’t they all your servants? Why do you want to do this? Why bring guilt on Israel?” (1 Chr 21:3). David’s need to count his people, like the compulsion of a miser to count his gold, speaks at once of possessive pride, and of neurotic insecurity. God has promised to preserve David’s kingdom. Why then should David worry about how many swords he can place in the field? In Chronicles, David in his righteousness was a model for the Chronicler’s community. So also, in his pride and rebellion, David stands as a warning. If even David could fall, and had to face the consequences of his failure, the Chronicler’s community needed to be all the more attentive and obedient to the will of the Lord.

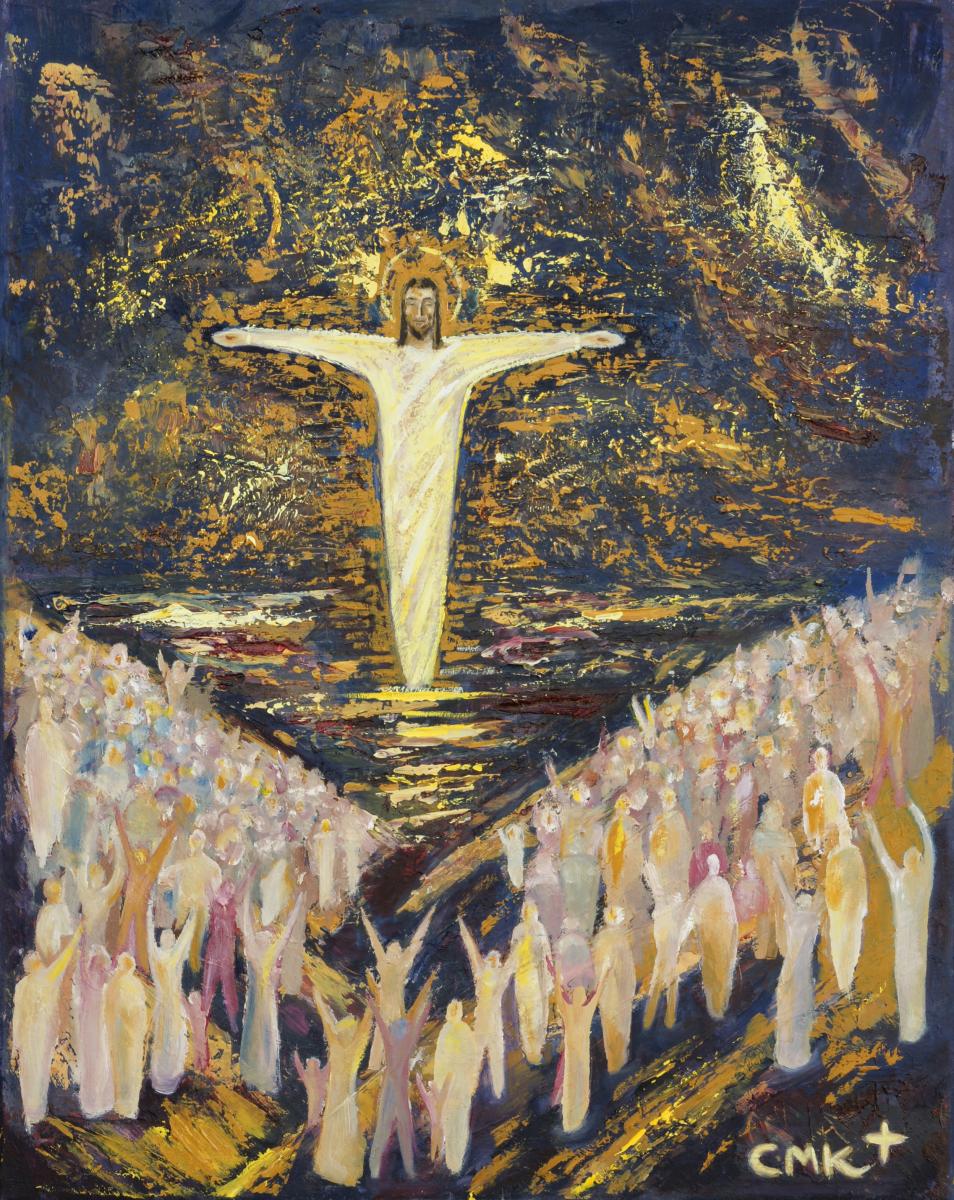

When, as in De Bois’ “Credo” and in Chronicles, the Devil stands for the deadly and seductive power of evil, this biblical image is appropriate, indeed necessary. But when we exalt Satan as a god to rival Christ, and when we demonize our earthly adversaries, denying their humanity, we fall guilty of idolatry, and forget the command of our Lord,

I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who harass you so that you will be acting as children of your Father who is in heaven. He makes the sun rise on both the evil and the good and sends rain on both the righteous and the unrighteous (Matthew 5:44-45).

This day, in the dead of winter, is associated with hope for the return of warmer weather–but not too soon. A “false spring” after all may be followed by a killing frost, wiping out trees that have budded too early, and threatening lambs born out of season. Therefore, sunny weather on this midwinter day (so that a groundhog can see its shadow!) is held to be a bad omen of more bleak days ahead, while cold and cloudy weather appropriate to the season augurs the swift return of sunshine and greenery.

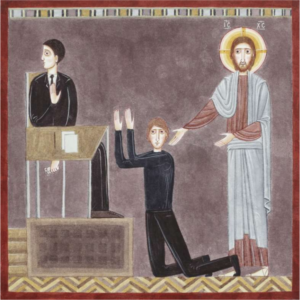

This day, in the dead of winter, is associated with hope for the return of warmer weather–but not too soon. A “false spring” after all may be followed by a killing frost, wiping out trees that have budded too early, and threatening lambs born out of season. Therefore, sunny weather on this midwinter day (so that a groundhog can see its shadow!) is held to be a bad omen of more bleak days ahead, while cold and cloudy weather appropriate to the season augurs the swift return of sunshine and greenery.![Title: Presentation in the Temple [Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/C_FirstSundayafterChristmas.jpg) This tapestry depicting Luke’s scene is from the Abbey Church of St. Walpurga in Virginia Dale, Colorado. The Order of St. Walpurga was established in the 11th century in Bavaria. The nuns of that order fled to the United States in 1935 to escape the Nazis, and settled in the Colorado mountains. The walls of their church are lined with tapestries like this one of the Presentation of the Lord, all inspired by biblical texts.

This tapestry depicting Luke’s scene is from the Abbey Church of St. Walpurga in Virginia Dale, Colorado. The Order of St. Walpurga was established in the 11th century in Bavaria. The nuns of that order fled to the United States in 1935 to escape the Nazis, and settled in the Colorado mountains. The walls of their church are lined with tapestries like this one of the Presentation of the Lord, all inspired by biblical texts. Although Jesus has come for everyone, not everyone will receive him. Simeon’s words prefigure Jesus’ coming rejection–his trial, condemnation, and crucifixion, and so Mary’s coming sorrow: “And a sword will pierce your innermost being too” (Luke 2:35). In this season after Epiphany, we rightly remember that Jesus’ way leads us to God’s light–but that way must pass through the darkness of the cross. Simeon offers no illusions that God’s salvation comes easily, without opposition or conflict.

Although Jesus has come for everyone, not everyone will receive him. Simeon’s words prefigure Jesus’ coming rejection–his trial, condemnation, and crucifixion, and so Mary’s coming sorrow: “And a sword will pierce your innermost being too” (Luke 2:35). In this season after Epiphany, we rightly remember that Jesus’ way leads us to God’s light–but that way must pass through the darkness of the cross. Simeon offers no illusions that God’s salvation comes easily, without opposition or conflict.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-1127577455-af4de78e939a40d9b37032ef9e24fd8a.jpg)

![Title: Silence [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/silencenmh9h5b8g7y7gh201.jpg) In the alternate Hebrew Bible reading for this Sunday (

In the alternate Hebrew Bible reading for this Sunday (

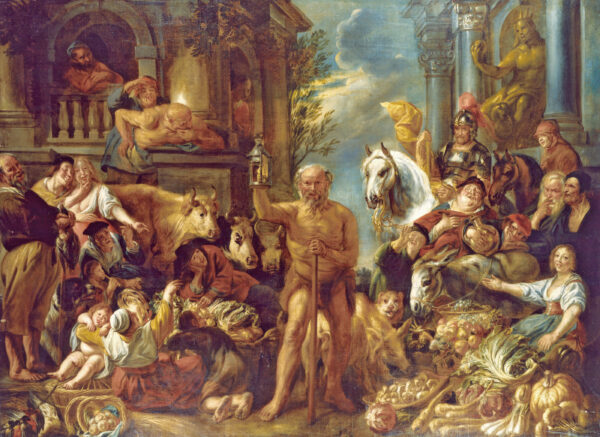

Here we go again! The Jack o’ lanterns, spooks, giant skeletons, and other holiday decorations in lawns and department store windows, the heaps of candy in grocery stores, the perennial return of pumpkin-spice-EVERYTHING–after Christmas, “Halloween” is the biggest commercial holiday of the year. But what many will not realize is that, like Christmas, Hallowe’en is properly a Christian celebration.

Here we go again! The Jack o’ lanterns, spooks, giant skeletons, and other holiday decorations in lawns and department store windows, the heaps of candy in grocery stores, the perennial return of pumpkin-spice-EVERYTHING–after Christmas, “Halloween” is the biggest commercial holiday of the year. But what many will not realize is that, like Christmas, Hallowe’en is properly a Christian celebration. Because of its association with Samhain,

Because of its association with Samhain,

Justice and vengeance have been on all our minds this month. On October 7, terrorists from the militant organization Hamas (the ruling political faction in Gaza) swept out of the Gaza Strip as far as 15 miles into Israel, attacking 22 farms, towns, and other communities; 1,400 Israelis were killed and 200 were taken hostage. More Jews were killed and wounded in this attack than on any other single day since the Nazi Holocaust.

Justice and vengeance have been on all our minds this month. On October 7, terrorists from the militant organization Hamas (the ruling political faction in Gaza) swept out of the Gaza Strip as far as 15 miles into Israel, attacking 22 farms, towns, and other communities; 1,400 Israelis were killed and 200 were taken hostage. More Jews were killed and wounded in this attack than on any other single day since the Nazi Holocaust.

The lid of the Ark was a slab of gold, molded in the image of two

The lid of the Ark was a slab of gold, molded in the image of two